This year there were a lot of announcements and commentary regarding government support for studies that may lead to actual development activities for space solar power. These events, as well as some efforts by private companies, have been prompted by global initiatives to reduce carbon emissions toward net zero by midcentury in the hope of mitigating climate change.

Last January Japan codified into law an aggressive timetable to launch an end-to-end space solar power demonstration flight in LEO by 2025. From an English translation of Japan’s Basic Space Law provided by the National Space Society, the exact text reads “Each ministry will work together to promote the realization of space solar power generation. Concerning microwave-type space solar power generation technology, the aim will be to demonstrate by 2025 energy transmission from low Earth orbit to the ground.” If implemented on time, this would be the first such technical demonstration to be performed from space. Also, the fact that the initiative is codified into Japan’s laws means they are serious.

At a Royal Aeronautical Society conference last April in London called Toward a Space Enabled Net-Zero Earth, chairman of the Space Energy Initiative Martin Soltau outlined a 12-year timeline that would provide gigawatts of power from space for the UK by 2035. The Initiative, which is a collection of over 50 British technology organizations, has selected a space solar power satellite design called CASSIOPeiA after a cost benefit analysis performed by Frazer-Nash Consultancy initially covered by SSP. Incidentally, links to the final report by Frazer-Nash Consultancy completed in September 2021 and to the CASSIOPeiA system are available on the SSP Space Solar Power page.

At the International Space Development Conference in Washington D.C. last May, Nickolai Joseph of the NASA Office of Technology Policy, and Strategy (OTPS) announced an effort by the space agency to reexamine space based solar power. The purpose of the study is to assess the degree to which NASA should support its development. Joseph said the report was to be completed by the end of September but as this post goes to press, it had not been released. Head of the OTPS, Bhavya Lal, tweeted last month that the report was in final review but this Tweet has been deleted without explanation. We are still waiting.

Three items on space solar power came up in September. First, John Bucknell returned to The Space Show to give an update on Virtus Solis, his space-based power system that SSP covered previously in an interview. With the novel approach of a Molynia sun-synchronous orbit, Bucknell claims that Virtus Solis will provide baseload capacity at far lower cost. In addition, the choice of orbits allow sharing orbital assets globally enabling solutions for multiple countries and regions. Bucknell hopes to have a working prototype to test in space within the next few years.

Later in the month, the American Foreign Policy Council published a position paper on space based solar power in the organization’s publication Space Policy Review. From the introduction, author Cody Retherford writes that space solar power “…satellites are a critical future technology that have the potential to provide energy security, drive sustainable economic growth, support advanced military and space exploration capabilities, and help fight ongoing climate change.”

Also in September, the European Space Agency proposed a preparatory program called SOLARIS to inform a future decision by Europe on space-based solar power. The proposal was submitted for consideration in November at the ESA Council at Ministerial Level held in Paris.

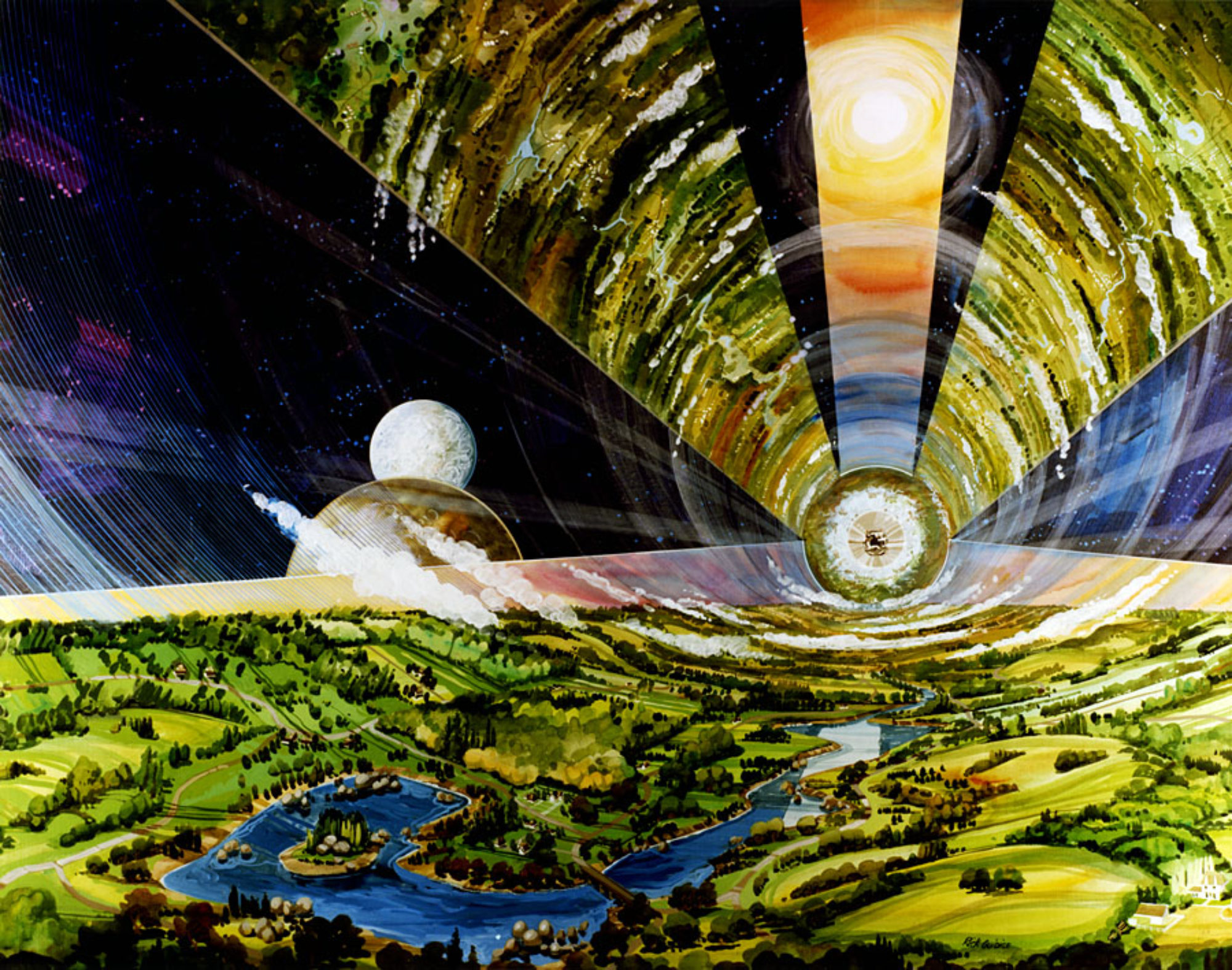

The goal of SOLARIS, conceptualized in the illustration at the top of this post, would be to lay the groundwork for a possible decision in 2025 to move forward on a full development program to realize the technical, political and programmatic viability of a space solar power system for terrestrial needs.

Upon the conclusion of the ESA Council at Ministerial Level meeting SOLARIS was approved as a program. The Council confirmed full subscription to the General Support Technology Programme, Element-1, which requested funding for SOLARIS development. The activities performed under Element 1 support maturing technologies, building components, creating engineering tools and developing test beds for ESA missions, from engineering prototype up to qualification. Still to be determined: how much funding will be allocated by each member of the EU.

Then in October an article published in Science asks the question “Has a new dawn arrived for space-based solar power?” The authors bring to light what many advocates have already realized: that better technology and falling launch costs have revived interest in the technology. Also in October, MIT Technology Review issued a report “Power Beaming Comes of Age”. Based on interviews with researchers, physicists, and senior executives of power beaming companies, the report evaluated the economic and environmental impact of wireless power transmission to flush out the challenges of making the technology reliable, effective and secure.

China announced in November that it plans to test space solar power technologies outside its Tiangong space station. Using the robotic arms attached to the station, they plan to evaluate on-orbit assembly techniques for a space-based solar power test facility which will eventually then orbit independently to verify solar energy collection and wireless power transmission. The China Academy of Space Technology has already articulated plans for development of their own space solar power system culminating in a 2 Gigawatt facility in geostationary orbit by 2050.

To cap off the year, aerospace engineer and founder of The Spacefaring Institute Mike Snead published a four-part series on evaluation of green energy alternatives including space solar power which he calls Astroelectricity. In the first part, he covers the history of humanity’s energy use and the dawn of fossil fuel use over the last century pointing out the fragility of the current system with respect to energy security. A gradual transition to fossil fuel free alternatives is needed to provide enough time for technology development and conversion over to green energy sources while not creating shocks to an economy based mostly on coal, oil and gas.

Next, nuclear power is addressed (and dismissed) as a green alternative with the next generation of smaller modular fission nuclear reactors currently under development. Due to waste heat challenges and nuclear weapons proliferation issues plus problems with scaling up enough of these power plants as base load supply to supplement intermittent wind and solar, this alternative is rejected as a viable green alternative. No mention is made of some the numerous fusion energy development activities in process or the promise of thorium molten salt reactors, so some readers may take issue with Snead’s position on this point.

In the third installment, if it is assumed that nuclear power is not a viable option, Snead examines to what extent wind and terrestrial based solar power has to be scaled up to replace fossil fuels in the latter part of this century given population growth and resulting energy needs. Not surprisingly, given the intermittent nature of wind and solar he finds these sources lacking, and they “… are not practicable options for America to go green.” Enter space solar power to fill the void.

In the last article in his series, Snead provides guidance for establishing a national energy security strategy for an orderly transition to green energy. He concludes that, “With America’s terrestrial options for going green not providing practicable solutions, the time for America to develop space solar power-generated astroelectricity has arrived. America now needs to pursue space solar power-generated astroelectricity to ensure that our children and grandchildren enjoy an orderly, prosperous transition to green energy.”

Finally, we close out the year with this: Northrop Grumman announced plans for an end to end space to ground demo flight in 2025 of their Space Solar Power Incremental Demonstrations and Research (SSPIDR) project funded by the Air Force Research Laboratory. SSP reported on the SSPIDR system previously. This development sets up a race between Japan, Virtus Solis (both mentioned above) and the U.S. government to be the first to beam power from space to the ground by the middle of this decade.