A mission architecture for Starship is described in a preprint open access article published online December 2 to be released in the next issue of the New Space Journal. The paper lays out a proposed strategy for using the yet to be validated SpaceX reusable spacecraft to establish a self sustaining colony on Mars. The authors* are a mix of space practitioners from NASA, the space industry and academia. No doubt Elon Musk may be thinking along these lines as he lays his company’s plans to assist the human race in becoming a multi-planet species.

Starship is a game changer. It is being designed from the start to deposit massive payloads on The Red Planet. It will be capable of delivering 100 metric tons of equipment and/or crew to the Martian surface, and after refueling from locally sourced resources, returning to Earth. This capability will not only enable extensive operations on Mars, it will open up the inner solar system to affordable and sustainable colonization.

Some of the assumptions posited for the mission architecture are based on Musk’s own vision for his company’s flagship space vehicle as articulated in the New Space Journal back in 2017, namely that two uncrewed Starships would initially be sent to the surface of Mars with equipment to prepare for a sustainable human presence.

“These first uncrewed Starships should remain on the surface of Mars indefinitely and serve as infrastructure for building up the human base.”

The initial landing sites will be selected based on where the water is. The priority will be finding and characterizing ice deposits so that humans will eventually be able to locally source water for life support and to produce fuel for the trip home. The automated payloads of these initial missions will be mobile platforms similar in design to equipment planned for upcoming robotic missions to the Moon in the next couple of years. One such spacecraft, the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) is discussed with its suite of instruments that will be used to assess the composition, distribution, and depth of subsurface ice to inform follow-on ISRU operations.

“The use of water ice for ISRU has been determined as a critical feature of sustainability for a long-term human presence on Mars.”

To harvest water from subsurface ice the authors suggest using proven technology such as a Rodriguez Well (Rodwell). In use since 1995, a Rodwell has been providing drinking water for the U.S. research station in Antarctica. The U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center’s (ERDC) Cold Region Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) has been working with NASA to prove the technology for use in space in advance of a human outpost on Mars.

“Rodwell systems are robust and still in routine use in polar regions on Earth.”

The next order of business is power generation. The authors suggest using solar power as a first choice because the technology readiness level is the most mature at this time. Autonomous deployment of a photovoltaic solar array would be carried out on the initial uncrewed missions. But due to frequent dust storms that could diminish the array reliability, nuclear power may be a more appropriate long term solution once space based nuclear power is proven. NASA’s Glenn Research center is working on Fission Surface Power with plans for a lunar Technology Demonstration Mission in the near future. A solid core nuclear reactor is also an option as the technology is well understood.

These initial missions will robotically assess the Martian environment at the landing sites to inform designs of subsequent equipment to be delivered by crewed Starship missions in future launch windows occurring every 26 months. Weather monitoring will be performed as well as measurements of radiation levels and geomorphology to inform designs of habitats and trafficability. Remotely controlled experiments on hydroponics will also be performed to understand how to produce food. Testing will be needed on excavation, drilling, and construction methods to provide data on how infrastructure for a permanent colony will be robustly designed.

Starship’s ample payload capacity will allow prepositioning of supplies of food and water to support human missions before self sustaining ISRU and agriculture can be established. Communication equipment will be deployed and landing sites prepared for the arrival of people. Much of these activities will be tested on the Moon ahead of a Mars mission.

Production of methane and oxygen in situ on Mars will enable refueling of Starship for the trip home, as envisioned in 1990 by Robert Zubrin and David Baker with their Mars Direct mission architecture. Zubrin’s Pioneer Astronautics may even play a role through provision of equipment for ISRU as they are already working on hardware that could be tested on the Moon soon. One could envision a partnership between Zubrin and Musk as their organizations have common visions, and Zubrin has written about the transformative potential of Starship. When people arrive on Starship during a subsequent launch window after the placement of uncrewed vehicles, further testing of ISRU and life support equipment will be performed with humans in the loop to validate these technologies that will enable Mars settlements to sustain themselves.

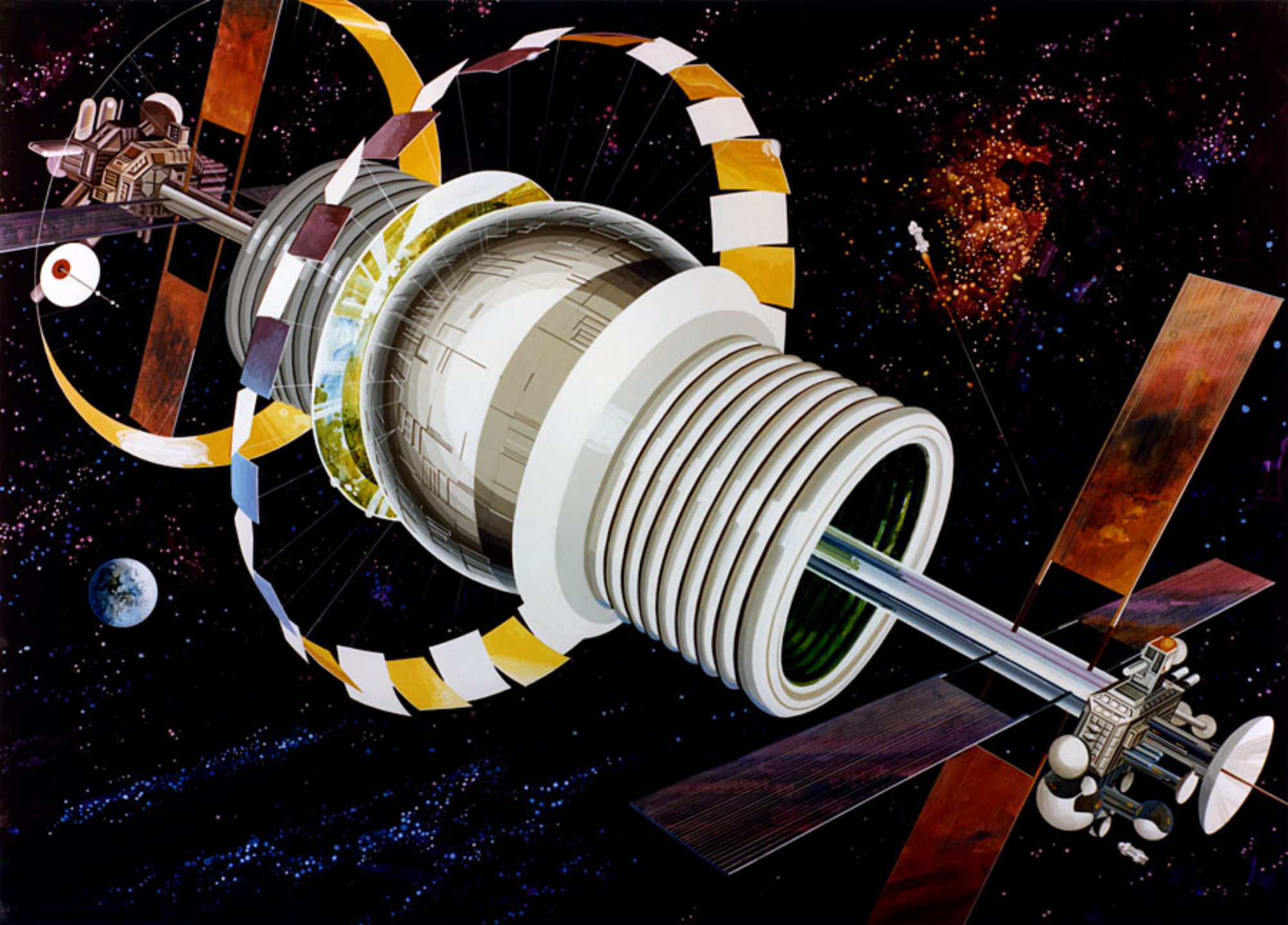

If Musk is successful in establishing a permanent self-sustaining colony on Mars will it be a true settlement? The National Space Society in their definition says that a space settlement “..includes where families live on a permanent basis, and…with the goal of becoming…biologically self-sustaining…”, i.e. capable of human reproduction. The definition is agnostic as to if the settlement is in space or on a planetary surface. Musk wants to established cities on the planet housing millions of people by mid century. But does this make sense if settlers can’t have healthy children in the lower gravity of Mars? SSP explored this question in a recent post. Hopefully, once Starship becomes operational, an artificial gravity research facility in LEO will be high on Musk’s priority list to answer this question before he gets too far down the Martian urban planning roadmap. Would he ever consider a change in space settlement strategy in favor of O’Neill type free space colonies? Starship could certainly help facilitate the realization of that vision.

If all goes according to plan, SpaceX will attempt the first orbital flight of a Starship prototype sometime next year, which also happens to be when the next launch window opens up for trips to Mars. Obviously, nothing in rocket development goes according to plan, so the initial flight ready design is at least a year away optimistically. And we know Musk’s timelines are notoriously aspirational. As ambitious as Musk is in driving his company toward the goal of colonizing Mars, it seems unlikely that an initial uncrewed mission with all its flight ready automated hardware as described above could be ready by the next launch window in 2024. But what about 2026? NASA’s current plans for return to the Moon call for a human rated version of Starship as a lunar lander “…no earlier then 2025”. However, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawathe’s Dear Moon mission sending 8 crew members around Luna with a crewed Starship is still planned for 2023. A lot of details are yet to be worked out and we still have not covered the topic of Planetary Protection nor the granting of a launch license to SpaceX by the FAA, but could a Starship human mission to Mars take place in 2028? Let me know what you think.

“The SpaceX Starship vehicle fundamentally changes the paradigm for human exploration of space and enables humans to develop into a multi-planet species.”

* Authors of Mission Architecture Using the SpaceX Starship Vehicle to Enable a Sustained Human Presence on Mars Jennifer L. Heldmann, Margarita M. Marinova, Darlene S.S. Lim, David Wilson, Peter Carrato, Keith Kennedy, Ann Esbeck, Tony Anthony Colaprete, Rick C. Elphic, Janine Captain, Kris Zacny, Leo Stolov, Boleslaw Mellerowicz, Joseph Palmowski, Ali M. Bramson, Nathaniel Putzig, Gareth Morgan, Hanna Sizemore, and Josh Coyan