Its a given that space travel and settlement are difficult. The forces of nature conspire against humans outside their comfortable biosphere and normal gravity conditions. To ascertain just how difficult human expansion off Earth will be, a new quantitative method of human sustainability called the Panscosmorio Theory has been developed by Lee Irons and his daughter Morgan in a paper in Frontiers of Astronomy and Space Sciences. The pair use the laws of thermal dynamics and the effects of gravity upon ecosystems to analyze the evolution of human life in Earth’s biosphere and gravity well. Their theory sheds light on the challenges and conditions required for self restoring ecosystems to sustain a healthy growing human population in extraterrestrial environments.

“Stated simply, sustainable development of a human settlement requires a basal ecosystem to be present on location with self-restoring order, capacity, and organization equivalent to Earth.”

The theory describes the limits of space settlement ecosystems necessary to sustain life based on sufficient area and availability of resources (e.g. sources of energy) defining four levels of sustainability, each with increasing supply chain requirements.

Level 1 sustainability is essentially duplicating Earth’s basal ecosystem. Under these conditions a space settlement would be self-sustaining requiring no inputs of resources from outside. This is the holy grail – not easily achieved. Think terraforming Mars or finding an Earth-like planet around another star.

Level 2 is a bit less stable with insufficient vitality and capacity resulting in a brittle ecosystem that is subject to blight and loss of diversity when subjected to disturbances. Humans could adapt in a settlement under these conditions but would required augmentation by “…a minimal supply chain to replace depleted resources and specialized technology.”

Level 3 sustainability has insufficient area and power capacity to be resilient against cascade failure following disturbances. In this case the settlement would only be an early stage outpost working toward higher levels of sustainability, and would require robust supplemental supply chains to augment the ecosystem to support human life.

Level 4 sustainability is the least stable necessitating close proximity to Earth with limited stays by humans and would require an umbilical supply chain supplementing resources for human life support, and would essentially be under the umbrella of Earth’s basal ecosystem. The International Space Station and the planned Artemis Base Camp would fall into this category.

Understanding the complex web of interactions between biological, physical and chemical processes in an ecosystem and predicting early signs of instability before catastrophic failure occurs is key. Curt Holmer has modeled the stability of environmental control and life support systems for smaller space habitats. Scaling these up and making them robust against disturbances transitioning from Level 2 to 1 is the challenge.

How does gravity fit in? The role of gravity in the biochemical and physiological functions of humans and other lifeforms on Earth has been a key driver of evolution for billions of years. This cannot be easily changed, especially for human reproduction. But even if we were able to provide artificial gravity in a rotating space settlement, the authors point out that reproducing the atmospheric pressure gradients that exist on Earth as well as providing sufficient area, capacity and stability to achieve Level 1 ecosystem sustainability will be very difficult.

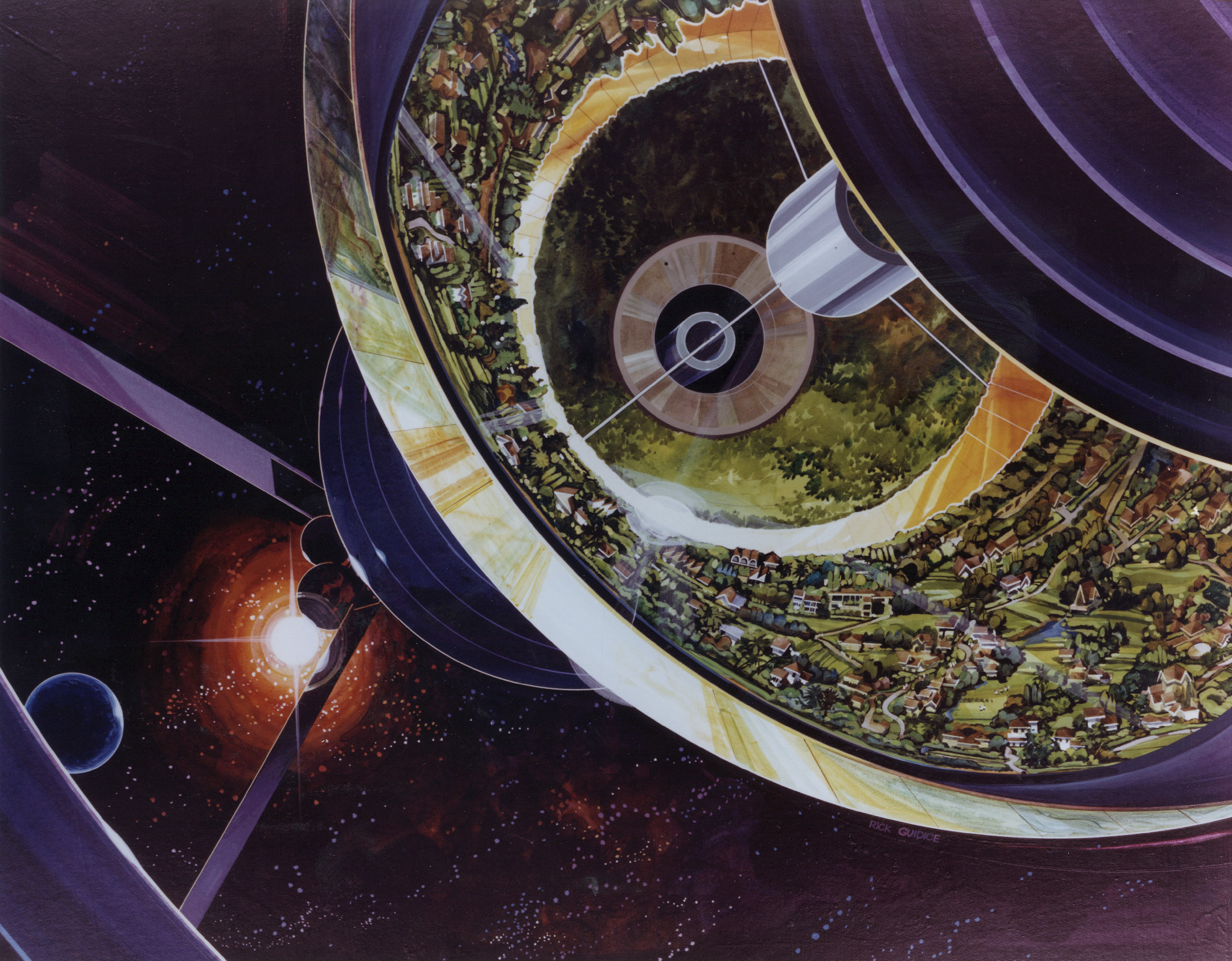

Peter Hague agrees that living outside the Earth’s gravity well will be a significant challenge in a recent post on Planetocracy. He has the view, held by many in the space settlement community, that O’Neill colonies are a long way off because they would require significant development on the Moon (or asteroids) and vast construction efforts to build the enormous structures as originally envisioned by O’Neill. Plus, we may not be able to easily replicate the complexity of Earth’s ecosystem within them, as intimated by the Panscosmorio Theory. In Hague’s view Mars settlement may be easier.

Should we determine the Gravity Rx? Some space advocates believe that knowledge of this important parameter, especially for mammalian reproduction, will inform the long term strategy for permanent space settlements. If we discover, through ethical clinical studies starting with rodents and progressing to higher mammalian animal models, that humans cannot reproduce in less than 1G, we would want to know this soon so that plans for the extensive infrastructure to produce O’Neill colonies providing Earth-normal artificial gravity can be integrated into our space development strategy.

Others believe why bother? We know that 1G works. Is there a shortcut to realizing these massive rotating settlements without the enormous efforts as originally envisioned by Gerard K. O’Neill? Tom Marotta and Al Globus believe there is an easier way by starting small and Kasper Kubica’s strategy may provide a funding mechanism for this approach. Given the limits of sustainability of the ecosystems in these smaller capacity rotating settlements, it definitely makes sense to initially locate them close to Earth with reliable supply chains anticipated to be available when Starship is fully developed over the next few years.

Companies like Gravitics, Vast and Above: Space Development Corporation (formally Orbital Assembly Corporation) are paving the way with businesses developing artificial gravity facilities in LEO. And last week, Airbus entered the fray with plans for Loop, their LEO multi-purpose orbital module with a centrifuge for “doses” of artificial gravity scheduled to begin operations in the early 2030s. Panscosmorio Theory not withstanding, we will definitely test the limits of space settlement sustainability and improve over time.

Listen to Lee and Morgan Irons discuss their theory with David Livingston on The Space Show.

Excellent article!