The Cislunar Science and Technology Subcommittee of the White House Office Science and Technology Policy Office (OSTP) recently issued a Request for Information to inform development of a national science and technology strategy on U.S. activities in cislunar space.

Dennis Wingo provided a response to question #1 of this RFI, namely what research and development should the U.S. government prioritize to help advance a robust, cooperative, and sustainable ecosystem in cislunar space in the next 10 to 50 years?

In a prolog to his response Wingo reminds us that historically, NASA’s mission has focused narrowly on science and technology. What is needed is a sense of purpose that will capture the imagination and support of the American people. In today’s world there seems to be more dystopian predictions of the future than positive visions for humanity. We seem to be dominated by fear of “…doom and gloom scenarios of the climate catastrophe, the degrowth movement, and many of the most negative aspects of our current societal trajectory.” This fear is manifested by what Wingo defines as a “geocentric” mindset focused primarily within the material limitations of the Earth and its environs.

“The question is, is there an alternative to change this narrative of gloom and doom?”

He recommends that policy makers foster a cognitive shift to a “solarcentric” worldview: the promise of an economic future of abundance through utilization of the virtually limitless resources of the Moon, Asteroids, and of the entire solar system. An example provided is to harvest the resources of the asteroid Psyche which holds a billion times the minable metal on Earth, and to which NASA had planned on launching an exploratory mission this year but had to delay it due to late delivery of the spacecraft’s flight software and testing equipment.

Back to the RFI, Wingo has four recommendations that will open up the solar system to economic development and address many of the problems that cause the geocentrists despair.

First, we should make the Artemis moon landings permanent outposts with year long stays as opposed to 6 day “camping trips”. This should be possible with resupply missions by SpaceX as they ramp up Starship launch rates (assuming the launch vehicle and lander are validated in the same timeframe, which seems reasonable). Next, we need power and lots of it – on the order of megawatts. This should be infrastructure put in place by the government to support commerce on the Moon. By leveraging existing electrical power standards and production techniques, large scale solar power facilities could be mass produced at low cost on Earth and shipped to the moon before the capability of in situ utilization of lunar resources is established. Some companies such as TransAstra already have preliminary designs for solar power facilities on the Moon.

Which brings us to ISRU. The next recommendation is to JUST DO IT. This technology is fairly straightforward and could be used to split oxygen from metal oxides abundant in lunar regolith to source air and steel. Pioneer Astronautics is already developing what they call Moon to Mars Oxygen and Steel Technology (MMOST) for just this application.

And lets not forget the wealth of in situ resources that could be unlocked via synthetic geology made possible by Kevin Cannon’s Pinwheel Magma Reactor.

Of course there is water everywhere in the solar system just waiting to be harvested for fuel and life support in a water-based economy.

Wingo’s final recommendation is industrialization of the Moon in preparation for the settlement of Mars followed by the exploration of the vast resources of the Asteroid Belt. He makes it clear that this is more important than just a goal for NASA, which has historically focused on scientific objectives, and should therefore be a national initiative.

“…for the preservation and extension of our society and to preclude the global fight for our limited resources here.”

With the right vision afforded by this approach and strong leadership leading to its implementation, Wingo lays out a prediction of how the next fifty years could unfold. By 2030 over ten megawatts of power generation could be emplaced on the Moon which would enable propellant production from the pyrolysis of metal oxides and hydrogen production from lunar water. This capability allows refueling of Starship obviating the need to loft propellent from Earth and thereby lowering the costs of a human landing system to service lunar facilities. From there the cislunar economy would begin to skyrocket.

The 2040s see a sustainable 25% annual growth in the lunar economy with a burgeoning Aldrin Cycler business to support asteroid mining and over 1000 people living on the Moon.

By the 2050s, fusion reactors provide power and propulsion while the first Ceres settlement has been established providing minerals to support the Martian colonies.

“The sky is no longer the limit”

By sowing these first seeds of infrastructure a vibrant cislunar economy will enable sustainable settlement across the solar system. A solarcentric development mythology may be just what is needed to become a spacefaring civilization.

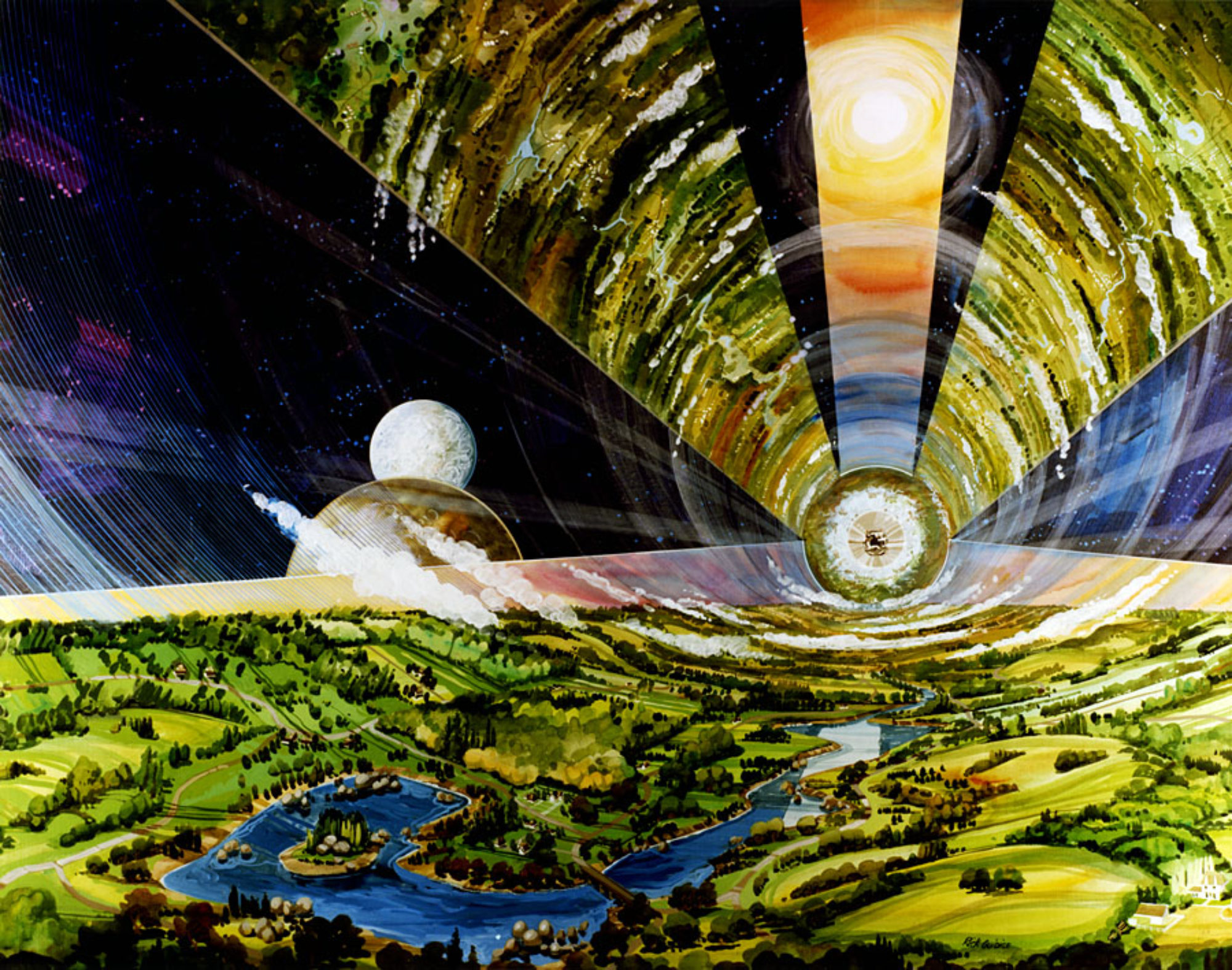

Artist’s concept of an O’Neill space colony. Credits: Rachel Silverman / Blue Origin