In response to ESA’s Open Space Innovation Platform Campaign on Clean Energy – New Ideas for Solar Power from Space, the Swiss company Astrostrom laid out a comprehensive plan last June for a solar power satellite built using resources from the Moon. Called the Greater Earth Lunar Power Station (GE⊕-LPS, using the Greek astronomical symbol for Earth, ⊕ ), the ambitious initiative would construct a solar power satellite located at the Earth-Moon L1 Lagrange point to beam power via microwaves to a lunar base. Greater Earth and the GE⊕ designation are terms coined by the leader of the study, Arthur Woods, and are “…based on Earth’s true cosmic dimensions as defined by the laws of physics and celestial mechanics.” From his website of the same name, Woods provides this description of the GE⊕ region: “Earth’s gravitational influence extends 1.5 million kilometers in all directions from its center where it meets the gravitational influence of the Sun. This larger sphere, has a diameter of 3 million kilometers which encompasses the Moon, has 13 million times the volume of the physical Earth and through it, passes some more than 55,000 times the amount of solar energy which is available on the surface of the planet.”

GE⊕-LPS would demonstrate feasibility for several key technologies needed for a cislunar economy and is envisioned to provide a hub of operations in the Greater Earth environment. Eventually, the system could be scaled up to provide clean energy for the Earth as humanity transitions away from fossil fuel consumption later this century.

One emerging technology proposed to aid in construction of the system is a lunar space elevator (LSE) which could efficiently transport materials sourced on the lunar surface to L1. SSP explored this concept in a paper by Charles Radley, a contributor to the Astrostrom report, in a previous post showing that a LSE will be feasible for the Moon in the next few decades (an Earth space elevator won’t be technologically possible in the near future).

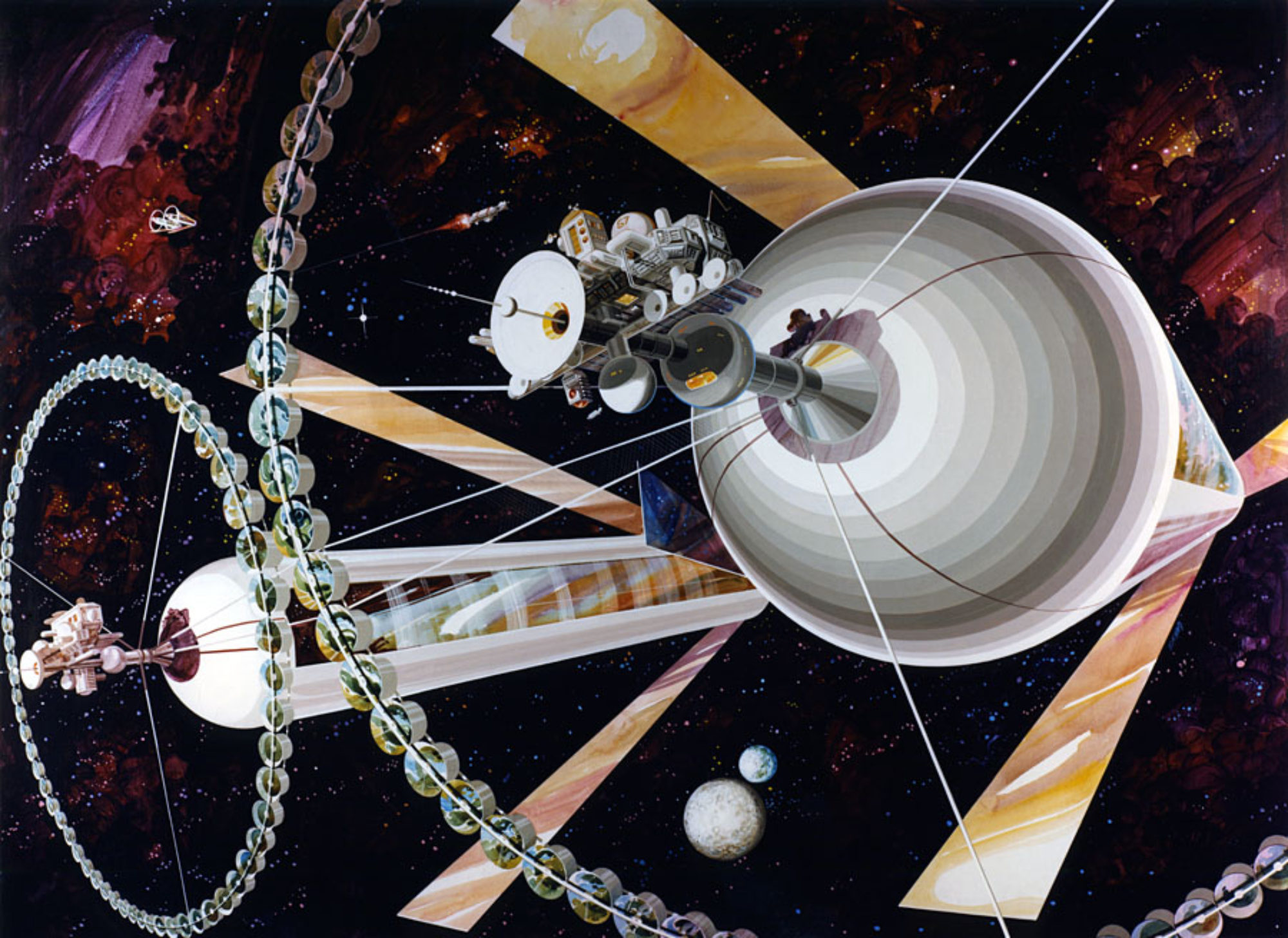

Another intriguing aspect of the station is that it would provide artificial gravity in a tourist destination habitat shielded by water and lunar regolith. This facility could be a prototype for future free space settlements in cislunar environs and beyond.

Fabrication of the GE⊕-LPS would depend heavily on automated operations on the Moon such as robotic road construction, mining and manufacturing using in situ resources. Technology readiness levels in these areas are maturing both in terrestrial mining operations, which could be utilized in space, as well as fabrication of solar cells using lunar regolith demonstrated recently by Blue Origin. That company’s Blue Alchemist’s process for autonomously fabricating photovoltaic cells from lunar soil was considered by Astrostrom in the report as a potential source for components of the GE⊕-LPS, if further research can close the business case.

Most of the engineering challenges needed to realize the GE⊕-LPS require no major technological breakthroughs when compared to, for example (given in the report), those needed to commercialize fusion energy. These include further development in the technologies of the lunar space elevator, in situ lunar solar cell manufacturing, lunar material process engineering, thin-film fabrication, lunar propellent production, and a European heavy lift reusable launch system. The latter assumes the system would be solely commissioned by the EU, the target market for the study. Of course, cooperation with the U.S. could leverage SpaceX or Blue Origin reusable launchers expected to mature later this decade. With respect to fusion energy development, technological advances and venture funding have been accelerating over the last few years. Helion, a startup in Everett, Washington is claiming that it will have grid-ready fusion power by 2028 and already has Microsoft lined up as a customer.

Astrostrom estimates that an initial investment of around €10 billion / year over a decade for a total of €100 billion ($110 billion US) would be required to fund the program. They suggest the finances be managed by a consortium of European countries called the Greater Earth Energy Organization (GEEO) to supply power initially to that continent, but eventually expanding globally. Although the budget dwarfs the European Space Agency’s annual expenditures ( €6.5 billion ), the cost does not seem unreasonable when compared to the U.S. allocation of $369 billion in incentives for energy and climate-related programs in the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act. The GE⊕-LPS should eventually provide a return on investment through increasing profits from a cislunar economy, peaceful international cooperation and benefits from clean energy security.

The GE⊕-LPS adds to a growing list of space-based solar power concepts being studied by several nations to provide clean, reliable baseload energy alternatives for an expanding economy that most experts agree needs to eventually migrate away from dependence on fossil fuels to reduce carbon emissions. Competition will produce the most cost effective system which, coupled with an array of other carbon-free energy sources including nuclear fission and fusion, can provide “always on” power during a gradual, carefully planned transition away from fossil fuels. The GE⊕-LPS is particularly attractive as it would leverage resources from the Moon and develop lunar manufacturing infrastructure while serving a potential tourist market that could pave the way for space settlement.