In a paper in the journal Sustainability a global team of researchers has created a two year curriculum to train the next generation of engineers who will design the chemical processes for the new industrial revolution expected to unfold on the high frontier in the next few decades.

Current chemical engineering (ChE) training is not adequate to prepare the next generation of leaders who will guide humanity through the utilization of material resources in space as we expand out into the solar system.

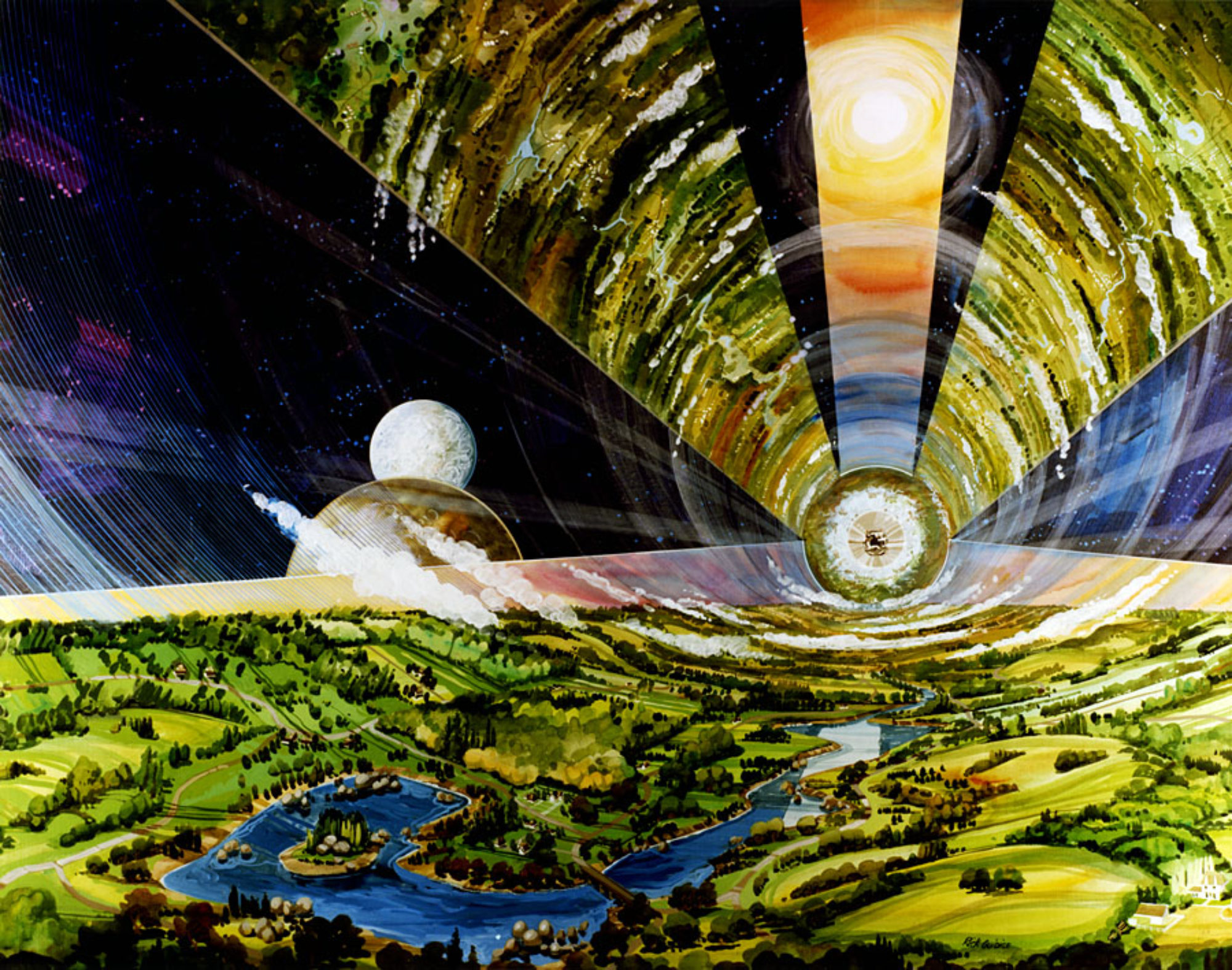

Astrochemical Engineering is a potential new field of study that will adapt ChE to extraterrestrial environments for in situ resource utilization (ISRU) on the Moon, Mars and in the Asteroid Belt, as well as for in-space operations. The body of knowledge suggested in this paper, culminating in Master of Science degree, will provide training to inform the design ISRU equipment, life support systems, the recycling of wastes, and chemical processes adapted for the unique environments of microgravity and space radiation, all under extreme mass and power constraints.

The first year of the program focuses on theory and fundamentals with a core module teaching the physical science of celestial bodies of the solar system, low gravity processes, cryochemistry (extremely low temperature chemistry), and of particular interest, circular systems as applied to environmental control and life support systems (ECLSS) to recycle materials as much as possible. Students have the option to specialize in either process engineering or a more general concentration in space science.

For the process engineering option in year one, students will learn how materials and fluids behave in the extreme cold of space. This will include the types of equipment needed for processes in a vacuum environment including microreactors and heat exchangers, as well as methods for separation and mixing of raw materials.

In the space science specialization, year one will include production of energy and its utilization in space. Applications include solar energy capture and conversion to electricity, nuclear fission/fusion energy, artificial photosynthesis, and the role of energy in life support systems.

In the second year, students learn basic chemical processes for ISRU on other worlds. Processes such as electrolysis for cracking hydrogen and oxygen from water; and the reactions Sabatier, Fischer-Tropsch and Haber-Bosche for production of useful materials.

The second year process engineering specialization focuses on ISRU on the Moon with ice mining, processing regolith and fluid transport under vacuum conditions. Propulsion systems are also covered including methane/oxygen engines, hydrogen logistics, cryogenic propellent handling in space and both nuclear thermal and electric propulsion. Space science specialization in year two covers life support systems and space agriculture.

A design project is required at the end of each year to demonstrate comprehension of the concepts learned in the curriculum, and is split between an individual report and a group project.

Coupled with synthetic geology for unlocking a treasure trove of space materials in the Periodic Table, innovative equipment for ISRU on the drawing board and research on ECLSS, Astrochemical Engineering will be a valuable skill set for the next generation of pioneers at the dawn of the age of space resource utilization.