Space Settlement Progress typically features the latest advancements in technology that are enabling the settlement of space. This post will be a little different. When attending the International Space Development Conference last May I was impressed by a team of students from Highschool Colegiul National Andrei Saguna in Romania, who had conceived of a space settlement in orbit around Jupiter’s satellite Ganymede which they call Minerva. The project was an entry in the National Space Societies’ Space Settlement Contest, and for which they won a second place award for 9th graders. While admiring their poster I was approached by Maria Vasilescu, who proudly described their project and agreed to collaborate with me on this post. She spoke perfect English, shared marketing materials (key chains, buttons and bookmarks with QR codes linking to their website) and explained that the primary purpose of Minerva would be a deep space location for a University of Space Exploration. I was intrigued by the concept and was struck by Maria and her teammates’ enthusiastic vision of humanity’s future in space. I wanted to know more about what motivated this group of teenagers to come together and create such an imaginative project, as youths like them will be future pioneers on the High Frontier. Maria agreed to coordinate with her team on an interview via email about Minerva.

SSP: How did the team come up with this Minerva concept?

Minerva: We took inspiration from our school which gave us a lot of opportunities to which we owe a lot and we wanted to build such a university in the final frontier.

SSP: You mentioned stumbling across some obstacles during your journey but sticking together by motivating each other. Is this an experience you feel comfortable sharing?

Minerva: One of the hardest things was to think about all the aspects that go into making a space settlement as ninth graders, such as the form [Forum on the website], which was decided in the last week, or the economical part. But we managed to meet often and brainstorm to come up with better ideas.

SSP: You said that the project helped you discover your true selves. Can you explain how this came about?

Minerva: We developed ourselves and our passions and we found out what we like because it covers a broad area of subjects beyond science. We managed to see by which area we are drawn to and enjoy actually researching.

SSP: You’ve stated that one of the reasons for building Minerva is to invent new lifestyles different from those that exist on Earth. How do you envision lifestyles changing in space?

Minerva: The university can prepare you for life in space, which will be an important part in the humans’ future, therefore we don’t want to invent new lifestyles, but incorporate space in the ones that already exist.

SSP: You’ve proposed auctioning a Minerva NFT to fund your efforts and future experiments. Would this be the sole source of financing for the project, and will it be sufficient? What about simply charging tuition for the USE?

Minerva: Everything on our settlement is given and made by us for the people so they don’t need to have money to buy material things. And because we have worked to make almost everything renewable and green, the funds MinervaNFT will bring are more than sufficient for everything else. And as for tuition, we feel like putting students through an exam such as the one that defines their attendance to USE is stressful enough as it is. However, the students will need to pay for the transport from Earth to the settlement.

SSP: There does not appear to be any trade or economic activity on Minerva, only academic studies. Students may choose to return to Earth or stay on the space station after they complete their studies. If they stay, have you considered the possibility of graduates developing and marketing other industries such as software development, robotics, mining water from Ganymede as rocket fuel, intellectual property on life support systems, or many other potential industries that could arise from scientific innovation that would take place on a space settlement? Or would this be totally an academic institution?

Minerva: It is not a totally academic institution because we have two thirds of the ship which will be occupied by students that remained on the settlement. But here, you don’t need money, everything being provided by us, so people don’t work for money, they work to occupy time, for enjoyment. If they do develop other industries, it will be fully for the greater good of humanity and the future of our kind, not for money.

SSP: The location chosen for Minerva is very challenging from an engineering perspective. Although Ganymede is not deep in Jupiter’s magnetosphere, and has its own magnetic field which could help mitigate exposure, the location will still have high levels of radiation if unprotected, which complicates the design because much more mass is needed to provide adequate shielding to be safe for humans. In addition, travel times to Jupiter are quite long even with improved propulsion which you’ve indicated would be as high as four years for students wanting to make the journey. Finally, solar energy at Jupiter’s remote distance from the sun requires that photovoltaic arrays be enormous to provide sufficient energy. A good compromise might be the asteroid Ceres, which is believed to be 25% water and does not have a magnetic field generating high radiation like what would be experienced at Jupiter. Others have proposed this asteroid as a good destination for space settlement. Why not locate the settlement in a more accessible and hospitable environment that might reduce costs?

Minerva: The main reason we chose such a far away location is precisely because we want to explore as much as possible of the cosmos. It’s not that we don’t want a closer location, it’s just that we know very little about Jupiter and its surrounding moons and further and this university can offer humanity an opportunity to explore it and send the research back to Earth. At the same time, we have taken the radiation into consideration and just how today’s spaceships have protection against it, so how [sic] our settlement, but ten times more efficient.

SSP: The sources of power for Minerva include solar arrays and nuclear fission, but you excluded fusion energy because it is currently experimental. By the time it will be technologically possible to travel to Jupiter and establish infrastructure that far out in the solar system, we will have developed fusion energy for use on Earth as well as in space. The preliminary design work for a Direct Fusion Drive for rapid transit to the outer planets has been started by Princeton Satellite Systems and the Fusion Industry Association just came out with their third annual report stating that the industry has now attracted over $6 billion in investment. When it is feasible to begin work on Minerva, fusion power sources will likely be available. Will you be updating your project plan as new technologies become available?

Minerva: Of course, we are sure that many aspects of our settlement can be improved by future developments in science, engineering and many other fields. As much as possible, we will incorporate them into our settlement. As mentioned in our paper, when talking about technological advances that may happen, we have to keep up with innovation and incorporate them to help us fulfill every need when travelling to space.

SSP: You raised the concern that Earth is approaching a major crisis with population growth putting a strain on Earth’s vital resources. You also said that the purpose of the space community is to sustain humanity if Earth’s environment became unfavorable for life. In selecting the location of Minerva, when considering Mars and its orbital distance, you said that even though it fulfills most of your requirements “…the disadvantage of Mars its it proximity to Earth…” and it “…is too close to our planet in order for us to choose it as the proper placement for the spacecraft.” Why must Minerva be distant from Earth if the planet is in crisis in the future and why isn’t the orbit of Mars, at 56 million kilometers, considered not far enough away?

Minerva: Mars wasn’t a viable option because, as we have stated before, the purpose of the USE is to gather information and scientific news that can only be found in the farther cosmos. We already know a lot about Mars and planets in close proximity to Earth, we want to venture further, discover and experiment with more than we already have.

SSP: Some surveys say that young people live in fear of the future due to climate change. Many media outlets amplify this doom and gloom. However, some economists point out that using the United Nation’s own data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, with the predicted increase in temperature by the year 2100, global GDP will be reduced by only 4% to deal with climate related impacts. Although it is clear that we should eventually reduce our dependance on fossil fuels this is not an existential threat. Plus, technological innovation continues to improve efficiency in resource utilization, energy development and agriculture, enabling higher standards of living notwithstanding increasing population growth.

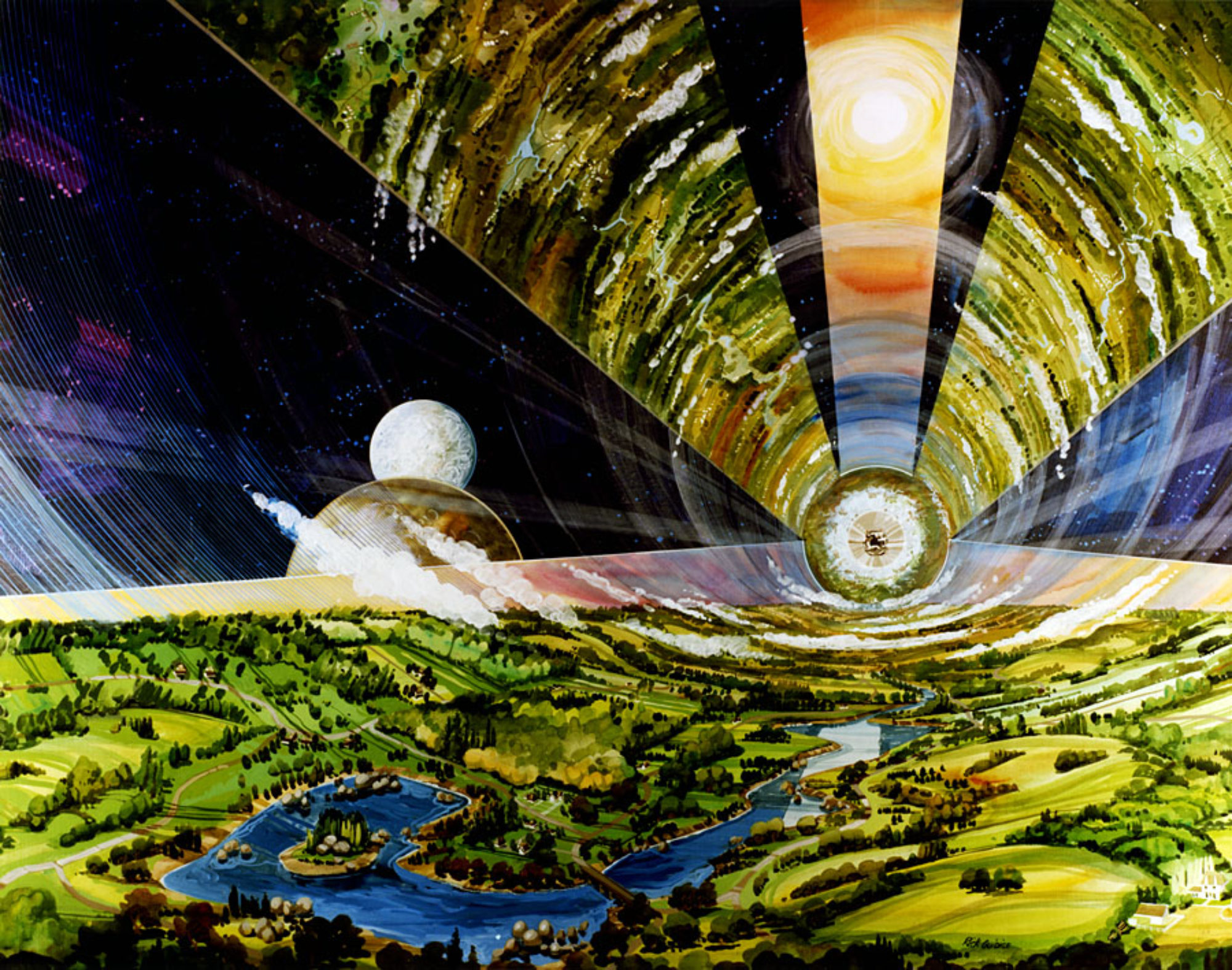

The viewpoint that the Earth is in “crisis” is closely aligned with Elon Musk’s motivation, who believes it is urgent that we become a multiplanetary species, to have a “Plan B” in case of a planetwide catastrophe. Jeff Bezos has a different perspective, that heavy industrial activity could be moved off world to preserve the Earth’s natural environment and to improve humanities’ standard of living though utilization of unlimited space resources.

Gerard K. O’Neill saw the promise of space settlement as a way to solve Earth’s problems through the humanization of space. He saw it as a way to end poverty for all humans, provide high-quality living space that would continue to grow robustly, to moderate population growth without war, famine, dictatorship or coercion; and to increase individual freedom. Does your team share the same anxiety about the future as other young people: that life on Earth is doomed and therefore, we need to build Minvera as a sanctuary to preserve humanity? Or do you see it as one among many options for space settlement to improve life on Earth and beyond, as outlined in O’Neill’s vision?

Minerva: We see Minerva as a place where people that are smart and passionate about space have a chance to make scientific discoveries that would be impossible to do on Earth. Aligned with Gerald O’Neil’s [sic] view, we believe that humans should expand into space whether it is as a Plan B or by harvesting resources from other planets or celestial objects. With the help of Minerva, the smartest children of their generation will be able to experience these scenarios and be closer to the future. We don’t see Minerva as a Plan B for humanity, students that have finished their 4 years being able to return to earth, but rather as a place where people can enjoy a stress free and enjoyable environment. Therefore Minerva is preparing smart youngsters to be able to take advantage of any of the two cases. If they choose to remain on Earth, the knowledge that they acquired while in the USE will definitely increase humanity’s survivability against the existential threats mentioned.

SSP: You’ve created a survey [what was earlier referred to as a “Form” and can be found at the “Forum” link on the Minerva website] for anyone to express their opinion about your project and the prospect of living in space. Will you use this feedback to improve your project?

Minerva: Maybe in the future, yes. We have encouraged people to complete the survey honestly and there’s always place for improvement for anything. And the second reason is to observe humanity’s view on such a settlement. In creating such a complex space settlement, you need to align your view with the society’s beliefs, them being the ones who will eventually populate it.

SSP: Does your team expect to remain engaged with the project as you progress in your education and after you eventually establish your careers here on Earth?

Minerva: It was certainly an experience we will treasure for a long time, but not everything has to be drawn out. I think this project took a lot of work and effort and we want to invest into something new, see this contest from as many angles as possible while we can. This project like no other can incorporate so many aspects of society from which you can discover your biggest passions. Talking to everyone in our group, we found that each one of us enjoyed a different part of the project and we believe that that was the key to our win. We were all doing something we are passionate about and therefore worked even harder for the final result. Now that we’ve learned what topics intrigue us, we can start doing even more work in that domain. We believe that this project is the perfect opportunity and will open numerous doors in any future career path. We strongly recommend this contest to anyone wondering whether they should put their effort into it or not.