At last year’s International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Aurelia Institute Vice President of Engineering Annika Rollock presented a paper on development of an orbital TESSERAE habitat to conduct biotechnology research. TESSERAE (Tessellated Electromagnetic Space Structures for the Exploration of Reconfigurable, Adaptive Environments) covered previously on SSP, was conceived and developed by Ariel Ekblaw, cofounder and CEO of Aurelia as part of her doctoral thesis at MIT. A TED Talk by Ekblaw from last April provides more detail on the concept with footage of prototypes demonstrated in space on the International Space Station (ISS).

The paper “Development of a Flight-Scale TESSERAE Habitat Concept for Biotechnology Research Outpost Applications” by Rollock, Max Pommier, William J. O’Hara, and Ekblaw, presents preliminary findings from a case study on the TESSERAE habitat which aims to bridge traditional space station architectures with future-oriented, adaptive designs. Legacy space habitats, such as the ISS, rely on monolithic hulls or cylindrical modules constrained by launch vehicle fairings, limiting scalability and geometric flexibility. TESSERAE offers a departure from these norms by using flat-packed, tile-based modules that self-assemble in orbit to form a truncated icosahedron. This structure, commonly known as a “buckyball” sharing the same shape as the carbon molecule buckminsterfullerene (C60) named after architect and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller due to its resemblance to his geodesic dome designs, will enable larger volumes and novel configurations when connected together.

The authors provide more detail on the concept referencing a trade study presented at ICES 2023 by the Aurelia Institute, which reviewed historical and contemporary space architecture to identify gaps and opportunities. They underscore the need for habitats that are both innovative and grounded in proven engineering principles. The paper serves as a “dynamic snapshot” of the ongoing TESSERAE case study as of spring 2024, inviting collaboration rather than presenting a finalized design. It envisions a platform based on TESSERAE as a commercial biotechnology research outpost in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), aligning with NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) goals and the burgeoning market for microgravity-enabled research. The paper highlights subsystem analyses for environmental control, thermal management, and power, alongside novel interior layouts informed by user research and terrestrial architecture best practices.

The authors make the case that self-assembling structures like TESSERAE could revolutionize human spaceflight by enabling adaptive environments that support diverse crews, including non-professional astronauts. This is particularly timely as the ISS nears decommissioning in 2031, necessitating new orbital platforms for critical research with increasing involvement by private industry..

The mission overview lays out one possible operational vision for the 2030s: a TESSERAE microgravity platform sustaining human life, scientific inquiry with a biotechnology focus, and ancillary activities in LEO. Designed for a crew of four—two biotechnologists and two career astronauts—it features biotechnology applications, capitalizing on microgravity’s unique properties for protein crystallization and biologic medicines production.

Protein crystal growth in space yields superior quality due to reduced sedimentation and convection, facilitating precise structural data for drug discovery. The paper references applications in treating among other maladies, muscular dystrophy, breast cancer, and periodontal disease, citing decades of ISS-based experiments by pharmaceutical firms. Similarly, biologic medicines—proteins, enzymes, nucleic acids, and antibodies derived from natural sources—benefit from low-gravity acceleration in discovery and preclinical testing. The global biologics market is projected to reach over $700 billion by 2030, underscoring the potential economic upside. Innovations like Redwire’s seed-based crystal manufacturing and Varda’s in-orbit ritonavir production (an HIV antiviral) have demonstrated feasibility, with microgravity enabling bulk-free returns via seeds or small samples.

The concept of operations (ConOps) details a 32-tile assembly (20 hexagons, 12 pentagons, each 2.26 m edge length, 0.46 m thick), launched in a dispenser stacked aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle. After dispensing out of the payload bay, orbital self-assembly employs electro-permanent magnets for bonding at the tile edges, forming a 493 m³ pressurized volume post-clamping and gasketing. Outfitting prioritizes autonomy: critical systems integrate into the tiles, with secondary elements (e.g., storage, mobility aids) added via robotics or minimal EVAs. After full systems checkout post-assembly, operations include 1–6 month crewed expeditions, cargo resupplies, and uncrewed intervals.

Comparative occupancy analysis positions TESSERAE favorably: at 123 m³ per person, it rivals the ISS (168 m³ for six) and Tiangong (113 m³ for three) emphasizing permanent quarters and lab space for its four-person upper limit, ensuring psychological and functional adequacy. This aligns with NASA’s CLD objectives, fostering commercial viability while accommodating “visiting scientists” alongside professionals.

With respect to interior concepts and design principles, TESSERAE’s non-cylindrical, open-central geometry introduces unique interior challenges and opportunities, diverging from conventional axial modules. The paper explores layouts tailored for diverse crews, drawing on user interviews (astronauts, analogue astronauts, scientists) and literature like Sharma et al.’s Astronaut Ethnography Project and Häuplik-Meusburger’s activity-based approach. Five core design principles and “desirements” guide this strategy: a human-centered approach accounting for bodily navigation and psychosocial needs; contextual affordances leveraging microgravity (e.g., multi-axis movement in open volumes); sensory mediation via lighting, acoustics, and airflow for zoned activities; accessibility with ample, clutter-free stowage; and a balance of permanence (fixed volumes) with flexibility (reconfigurable elements like folding partitions).

These principles inform environmental mediations for biotechnology: labs require vibration isolation and containment for experiments, while communal spaces mitigate isolation via views and biophilic design elements. The paper discusses layouts prioritizing flow, orientation, and adaptability. One configuration features a central “node” for socialization and exercise, ringed by radial spokes: private quarters, labs, hygiene nodes, and utility closets embedded in the shell. This exploits the buckyball’s symmetry for efficient use of space, with tethers and handrails guiding microgravity transit. Labs allocate ~100 m³ total, segmented for crystallization (vibration-dampened gloveboxes) and biologics (flow benches, incubators), in accordance with preliminary user needs.

Sensory design mitigates monotony: variable LED lighting simulates diurnal cycles, acoustic panels dampen noise, and materiality ( e.g., fabric panels) enhances tactility. Stowage integrates nets and modular racks, addressing chronic ISS issues. Flexibility allows crew reconfiguration via magnetic mounts, supporting mission evolution. Hygiene and galley zones emphasize efficiency, with water-efficient fixtures tied to the Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS). Overall, interiors blend spacecraft rigor with architectural humanism, fostering well-being for non-experts.

The authors provide a subsystem analysis discussing trades for ECLSS, thermal control, and power. ECLSS recommendations draw from ISS heritage leveraging NASA’s Carbon Dioxide Removal and Oxygen Generation Assemblies but adapt to TESSERAE’s modularity: distributed nodes per each individual tile reduce single-point failures, with regenerative loops for water and air.

Thermal management addresses the buckyball’s high surface-area-to-volume ratio, prone to radiative losses. Multi-layer insulation and variable-emittance coatings are proposed, integrated into tiles for passive control, supplemented by active radiators and heat exchangers. Finite element modeling was used to inform stress distribution across the tile seams.

Power generation leverages roll-out solar arrays deployed post-assembly, sized for 20–30 kW demands for the needs of the labs, ECLSS and other power systems. Trades evaluate photovoltaics vs. emerging tech, prioritizing launch mass. Batteries buffer eclipse periods, with guidance navigation integrated with attitude control via control gyroscopes, minimizing propellant use.

These analyses emphasize scalability: TESSERAE’s tiles enable redundant, upgradable subsystems, contrasting with legacy monolithic designs.

The paper identifies a few challenges. For instance, assembly reliability (magnet actuation in vacuum), pressurization integrity at seams, and outfitting logistics. But opportunities abound in biotech such as enabling “fly-your-own-experiment” for scientists, accelerating drug pipelines, and demonstrating adaptive habitats for lunar/Mars precursors. User research highlights psychosocial needs—privacy amid openness, sensory variety against confinement—which will inform iterative designs.

Future work matures hardware testing in microgravity (e.g., parabolic flights), refines trades via modeling, and pursues partnerships for CLD certification. The authors invite input, positioning TESSERAE as a collaborative pivot toward reconfigurable space living.

This case study encapsulates one of TESSERAE’s promises: a self-assembling, biotech-focused habitat merging innovation with pragmatism. By the 2030s, it could sustain crews in 493 m³ of adaptive volume in LEO, tapping into a $700B+ market while advancing human-centered space architecture. Preliminary insights from this work — from ConOps to design of interiors— lay the groundwork for transformative outposts that not only return benefits to human lives on Earth, but are preparing humanity to become a spacefaring species.

While the Aurelia Institute is a nonprofit organization, Ariel Ekblaw cofounded a startup called Rendezvous Robotics which aims to generate revenue building large-scale structures like antenna apertures, space solar power arrays and orbital data centers, all autonomously fabricated in space using TESSARAE. Rendezvous Robotics recently partnered with another startup called Starcloud which plans to fabricate gigawatt-scale orbital AI data centers using Ekblaw’s invention, a potentially huge new market forecasted to be just over the horizon by several tech leaders in the news recently. Blue Origin CEO Jeff Bezos just announced he’ll be leading a new AI company called Project Prometheus and says AI orbital data centers are coming in the next decade or two. Last May former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt acquired Relativity Space to put data centers in orbit. Earlier this month Elon Musk says in not more than 5 years, the lowest cost way to do AI compute, will be in space. And Mach33 Research, an investment research firm focused on the industrialization of space, predicts that orbital compute energy will be cheaper than on Earth by 2030. TESSARAE could be leveraged to assemble these space-based hyperscalers autonomously and quickly while proving out this reconfigurable technology which can be used to build large-scale adaptable habitats and other infrastructure in space for a multitude of applications. As stated on the their website,

“Aurelia is working toward geodesic dome habitats, microgravity concert halls, space cathedrals—the next generation of space architecture that will delight, inspire, and protect humanity for our future in the near, and far, reaches of space.”

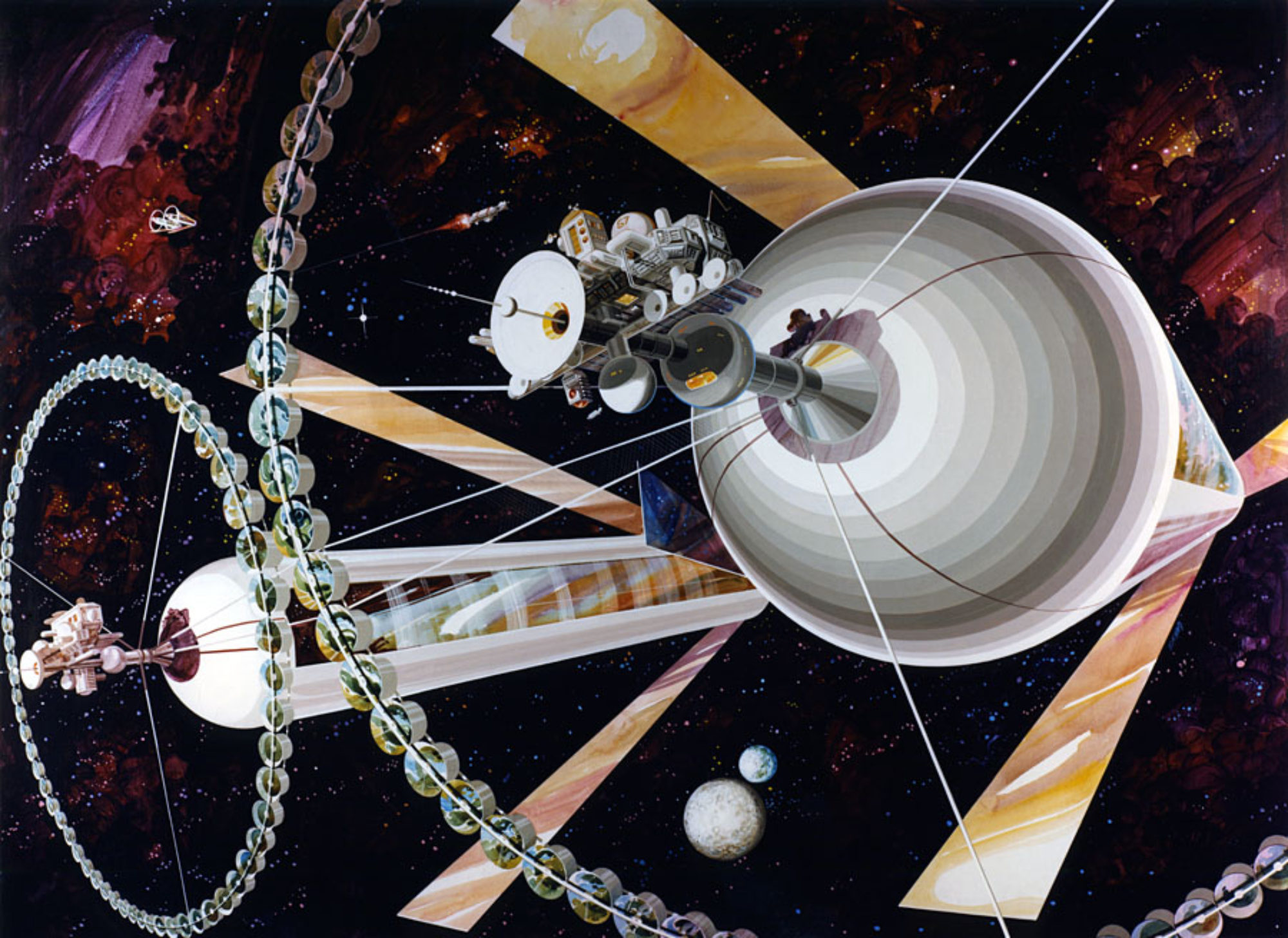

Finally, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the 1975 NASA Space Settlements: A Design Study, the Institute announced today they are sponsoring The Aurelia Institute Prize in Design for Space Urbanism. An award of up to $20,000 will granted for concepts of a functioning space station in one of three categories: A space station in LEO or at a Lagrange point; a space habitat in lunar orbit or on the surface of the Moon; or an automated industrial facility (e.g. focused on space mining, energy, biotech, etc.) in one of those locations.