Space News recently reported that Colorado-based Lunar Outpost has signed an agreement with SpaceX to use Starship to deliver their lunar rover, known as the Lunar Outpost Eagle, to the Moon. Announced November 21, the contract supports the Artemis program with surface mobility and infrastructure services. The agreement positions Starship as the delivery vehicle for Lunar Outpost’s Lunar Terrain Vehicle (LTV), which is a contender for NASA’s Lunar Terrain Vehicle Services (LTVS) program. The exact terms of the contract, including the launch schedule, were not disclosed in the announcements. Lunar Outpost has assembled a contractor team under the banner “Lunar Dawn” to execute the company’s LTV solution. The collaborative development program includes in industry leaders Leidos, MDA Space, Goodyear, and General Motors.

Rover Design Features

- Mobility and Functionality: The Lunar Outpost Eagle is designed to support both crewed and autonomous navigation on the lunar surface. It’s built to operate even during the harsh lunar night, exhibiting resilience against the Moon’s extreme temperature changes.

- Collaborative Development: The Lunar Dawn team brings expertise in spacecraft design, robotics, automotive technology, and tire manufacturing, ensuring a robust and versatile design.

- Size and Capacity: Described as truck-sized, the Eagle LTV is intended to be a valuable vehicle for lunar operations, capable of transporting heavy cargo to support NASA’s Artemis astronauts and commercial activities.

- Testing and Refinement: The design has undergone human factors testing at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, with feedback from astronauts being used to refine the vehicle’s usability and functionality.

Future Plans

- NASA’s LTV Program: Lunar Outpost is one of three companies selected by NASA for the LTV program to develop rovers to support future Artemis missions. The other two companies are Intuitive Machines and Venturi Astrolab. After a preliminary design review (PDR), NASA will select at least one company for further development and demonstration, with the goal of having a rover operational in time for Artemis 5, currently scheduled for 2030.

- Commercial Operations: Beyond NASA’s usage, the rovers will be available for commercial operations when not in use by the agency, aiming to support a sustainable lunar economy. This includes plans for infrastructure development and scientific exploration.

- Series A Funding: Lunar Outpost has recently secured a Series A funding round to accelerate the development of the Lunar Outpost Eagle, ensuring that the rover project moves forward regardless of the outcome of NASA’s selection process.

- Long-Term Vision: The company’s vision extends to enabling a sustainable human presence in space, with plans to leverage robotics and planetary mobility for development of infrastructure to harness space resources.

This partnership with SpaceX and the development of Eagle under the Lunar Dawn program are pivotal steps in advancing both NASA’s lunar exploration goals and commercial activities on the Moon.

Once delivered to the Moon by Starship, the Eagle rover will drive over harsh regolith terrain which, as discovered by Apollo astronauts when driving the Lunar Roving Vehicle, presents several unique challenges due to the Moon’s distinct environmental conditions. First, lunar dust is highly abrasive and can become electrostatically charged sticking to surfaces and mechanisms resulting in wear and degradation of wheels, bearings, and sensors potentially leading to equipment failure. The Moon’s low gravity can make traction difficult. Rovers might slip or skid becoming less stable when accelerating, braking or turning. Terrain variability and nonuniformity on loose powdery dust or sharp, rocky outcrops could cause stability issues.

These problems can be solved by creating roads with robust, smooth surfaces for safe and reliable mobility on the Moon. Initially, the regolith could be leveled by robots with rollers to compact the regolith to make it less likely to be kicked up by rover wheels. Eventually, technology being developed by companies like Ethos Space for infrastructure on the Moon using their robotic system for melting regolith in place for fabricating lunar landing pads, could be used to build smooth, stable roads.

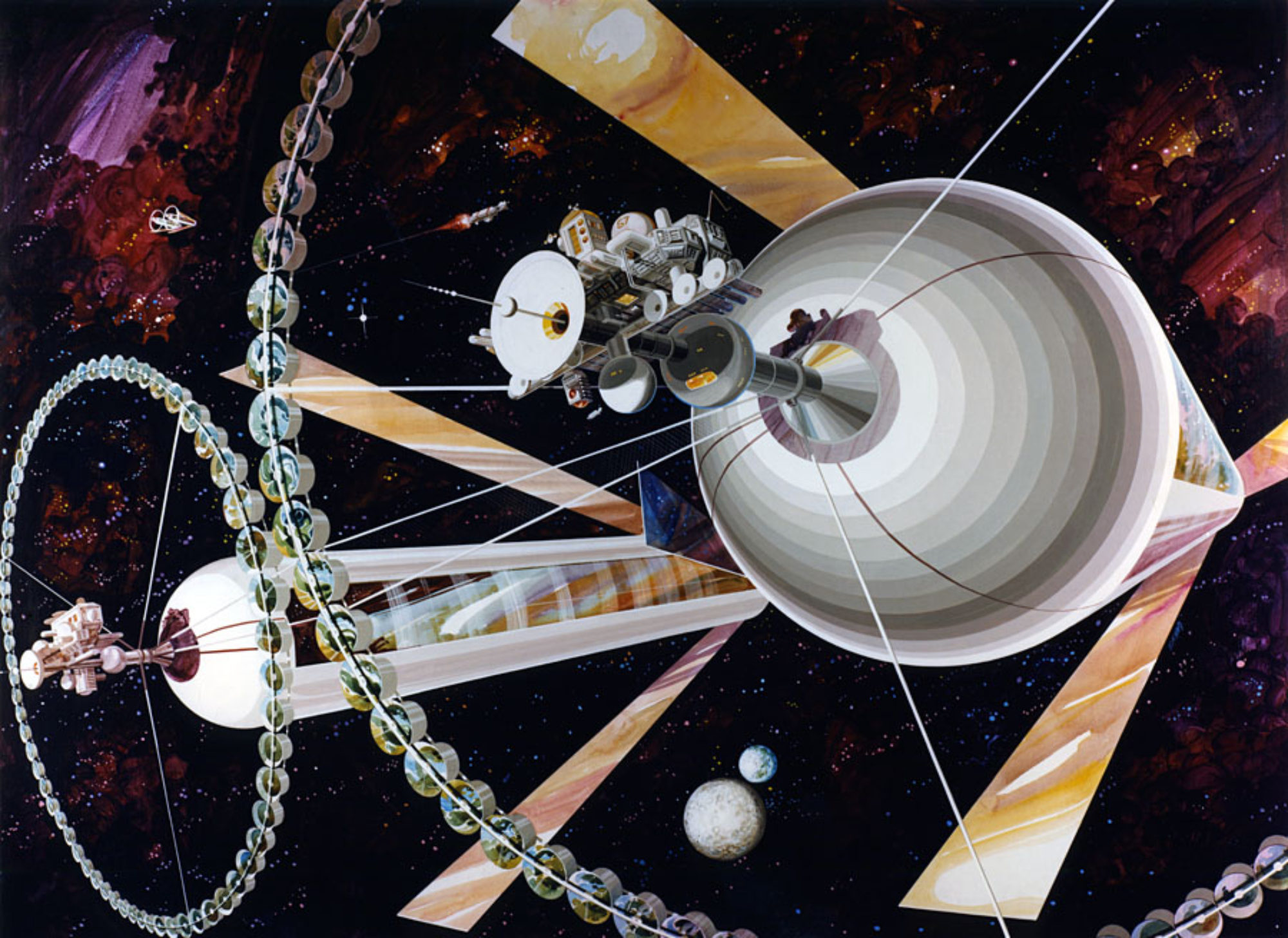

A network of roads could be constructed to transport water and other resources harvested at the poles to where it would be needed in settlements around the Moon extending from high latitudes down to the equatorial regions. As envisioned by the Space Development Network, this system of roads could be created to provide access to a variety of areas to mine valuable resources as well as thoroughfares to popular exploration and tourism sites. The development of the highway system could start at the poles with telerobots, then eventually be expanded to include equatorial areas and would be fabricated autonomously prior to the arrival of large numbers of settlers.

Longer term, a more efficient method of transportation on the Moon could be magnetic levitation (maglev) trains. Research into this technology has already been proposed by NASA which is actively developing a project named “Flexible Levitation on a Track” (FLOAT), which aims to create a maglev railway system on the lunar surface. This system would use magnetic robots levitating over a flexible film track to transport materials, with the potential to move up to 100 tons of material per day. The FLOAT project has advanced to phase two of NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program.