I met Kent Nebergall during a cocktail reception at ISDC which took place May 27-29. He chairs the Steering Committee for the Mars Society (MS) and gave a fascinating talk Sunday afternoon on Creating a Space Settlement Cambrian Explosion. We had a wide-ranging discussion on some of his visions for space settlement and he agreed to collaborate on this post. We’ll do a deep dive into some of the topics he covered in his talk, which is available on his website at MacroInvent.

In summary, he breaks down some of the key challenges of space settlement and proposes economic models for sustainable growth. His roadmap lays out a series of space settlement architectures starting with a variant of SpaceX Starship used as a building block for large rotating habitats and surface bases for the moon, Mars, and asteroids. Next, he presents his Eureka Mars Settlement design which was entered in the MS 2019 Mars Colony Design Contest addressing every technical challenge. Finally, an elegant system for para-terraforming Martian canyons in multi-layered habitats is proposed, “…with the goal of maximizing species diversity and migration beyond our finite world. We not only preserve and diversify species across biomes, but engineer new species for both artificial and exoplanetary habitats. This is an engine for creating technology and biological revolutions in sequence so that as each matures, a new generation is in place to keep driving expansion across the solar system and beyond.”

Here’s my interview with Kent conducted via email. I hope you enjoy it!

SSP: You created a checklist of the required technologies needed to enable space settlement where each row is sorted by increasing necessity while the columns are sorted by greater isolation from Earth.

Musk has started to crack the cheap access to space nut and large vehicle launch at upper left with Starship but we’re not there yet. Given that Musk’s timelines always should be taken with a grain of salt, and the challenge of planetary protection (bottom of column 3) could potentially prevent Musk from obtaining a launch license for a crewed mission before scientists have a chance to robotically search for signs of life, what is your estimation of the probability that Humans will land on Mars by 2029, in accordance with your proposed timeline (see below)?

KN: Elon time is real, definitely. My outside analysis implies that SpaceX is using Agile development systems borrowed from the software industry. The benefit of Agile is that technological progress is as fast as humanly possible. The bad news is that it largely ignores things that traditional management styles value, such as being able to predict the date something is really finished. At any rate, my general conclusion is that anything Elon predicts will be off by 43 percent as a baseline, assuming no outside factors are involved. Starship has slid more because the specifications kept changing, much as they did with Falcon Heavy.

We seem to be locked in on the early orbital design, which seems to be purely for getting Starlink 2 satellites in place and providing return on investment while getting the core flight systems refined. It doesn’t need solar panels, crew space, or the ability to stay on orbit more than a day. Crewed Starship may take another few years and use a smaller than expected cabin with a large payload bay. 2029 is the most recent year of a crewed Mars landing from Elon (as of March, 2022). If we allow for Elon Time, we could expect cargo in that launch window. I suspect one vehicle may try to return to prove out that flight range, like return to Earth from deep space. The first mission would largely be watching Optimus Prime robots setting up a farm of solar panels to make fuel for the return trip.

“The irony is that Elon could just pack the ship with Tesla humanoid robots for the first few missions…”

The planetary protection regulatory barrier is quite possible, yes. We just saw the regulatory findings for Bocca Chica. That requires several frivolous preconditions for flight, like writing an essay on historic monuments and accommodating ocelots, which haven’t been seen in the area in forty years. I doubt the capacity of political Simon Says playground games like has been exhausted yet.

What we’ve seen historically is that those who cannot compete will throw up regulatory and legal barriers. However, we’ve also seen that these efforts eventually burn out after a few years. This has been true with paddle wheel river ships, steam ships, railroads, and airlines. It’s playing out with Tesla and the big three domestic automakers now as well. Most of those tricks were already pulled with Falcon 9, so I think that path is largely burned through. I’m nearly certain they will try the planetary protection argument later. We have already seen with the ocelots that they are willing to protect absent species.

The irony is that Elon could just pack the ship with Tesla humanoid robots for the first few missions and build a base while running life searches in the area. The base could be built with nearly the same productivity as a human crew, and the cultural pressure to move humans into it would be quite high if no life is found in the meantime. It would be great marketing for the Tesla robots as well.

SSP: The table seems comprehensive and covers just about everything. Has it changed or been updated in 18 years? I noticed “Spacesuit Lifespan”. Why is this a challenge for space settlement?

KN: The table is fairly solid in terms of subject matter, but I’ve started a project to rebuild it. I only found out recently that NASA’s term for this is RIDGE (Radiation, Isolation, Distance, Gravity and Environment). My slicing into 26 categories is more precise – literally an alphabet of categories.

First, if it were a true “periodic table” analog, it would transpose the columns. But it’s much easier to fit in PowerPoint this way. Second, I have used this principle for other challenge sets and found interesting implications, so I may make a more advanced version in the future with far more depth. I’ll still use this for PowerPoint, though, because it can be read from the back row in under a minute. Third, each “challenge” is actually a family of challenges. There are multiple health problems with microgravity, for example, but one root cause – the absence of gravity. So, while each challenge in the table has many sub-factors, there is a single root cause and a solution that eliminates that cause also eliminates all sub-sets of problems. If a solution cannot fix the root cause, than separate solutions are needed for each child challenge like bone loss.

Spacesuit lifespan for the ISS is an issue because the suits are often older than the station itself. On the moon, the spacesuits picked up abrasive moon dust in the joints and could have eventually lost flexibility or pressure integrity if they’d been used much longer. A Mars suit is in some ways easier because the soil is more weathered and therefore less abrasive. Space settlement hits a standstill if you can’t go outside. Unfortunately, efforts to replace them have cost a billion dollars so far and have just been restarted for an even higher price tag. It seems to be the classic example of doing as little progress as possible while spending as much money as possible. There have been some great technologies developed but there has been no pressure to finish a completed suit. As the old saying goes, “One day, you just have to just shoot the engineer and cut metal”.

At one point, SpaceX outright said, “We can do it.” But NASA showed no interest, and SpaceX apparently didn’t bid on the moon suit designs this time. They have been converting the ascent suit from Dragon to one able to do spacewalks in the 1960’s Gemini sense for launch this year. I wouldn’t be surprised if they develop a moon suit just because they can, and on their own dime. It would be quite embarrassing for all involved, including SpaceX, if we had a 100 tonne payload moon lander capable of holding dozens of people, and not have a single suit capable of letting them leave the ship.

SSP: You mentioned orbital debris being a potential barrier for your plan’s LEO operations and you’ve come up with methods for shielding early orbital habitats, but they may not be effective against larger debris fragments. The X-prize Foundation is considering an award for ideas to solve this problem and there are numerous startups on the verge of addressing the issue. Such a solution would have to be implemented quickly and on a massive scale for your timeline to be achieved. If orbital debris looks like it may still be a problem for larger orbital settlements until they can be established in higher orbits, could your plan be modified to perhaps include debris removal as an economic driver? [SpaceX president and COO Gwynne Shotwell has suggested that Starship could be leveraged to help clean up LEO]

The problem must be sliced up, just as the other grand challenges are sliced up. We need several approaches at once. First, refueling starship is a bit risky, and the risk rises with prolonged exposure to the debris hazard. SpaceX originally wanted to launch the Mars vehicle, then refuel it on orbit over several tanker flights. More recently, they are implying they would fly a tanker up, fill it with several other tankers, then refuel the Mars or Lunar vehicle in one go. This makes a lot more sense. A tanker or depot hit by debris would be a space junk hazard, but it wouldn’t cost lives or science hardware.

We need to de-orbit the largest items, many of which are spent rocket stages. SpaceX has offered to gobble them up with Starship, but that means a lot of delta V in terms of altitude, inclination, elliptical elements, and so on. I could see a sort of penny jar approach where they drop off a satellite, then pick up an old one or two (the satellite and old rocket stage) before returning. Realistically, though, old rocket stages and satellites that haven’t vented every single tank (main and RCS [reaction control system]) will be hazardous to approach.

It seems the best solution would be mass-produced mini-satellites with ion drive and electrodynamic tethers. Each mini-sat would find a spent rocket stage or defunct satellite and add an electrodynamic tether to drag it down using Earth’s magnetic field while also powering an ion engine to assist in de-orbiting. You would have to do a few at a time because the tethers themselves would become a hazard if we had thousands of them cutting through space like razor ribbons.

I could also see a spider robot that would grab larger satellites with propellant still on board, wrap them up like a spider wrapping a bug in silk, and then puncturing the tanks carefully to both refill itself and render the satellite inert. It would then be safe to grab with a Starship or de-orbit with a drag or propellant system [Another concept for debris removal could be Bruce Damer’s SHEPHERD which we covered a year ago. Although originally conceived for asteroid capture, a pathfinder application could be satellite servicing/decommissioning].

We didn’t create the problem in a day, and we can’t solve it quickly either. But we can take an approach of de-orbiting two tons for every ton launched once we have mass produced systems for doing so. Maybe other launch providers can grab defunct satellites with their orbital launch stages before dragging them both into the Pacific.

That said, we can’t get every paint chip and bolt out of orbit this way. We will hit a law of diminishing returns. Anything below that line will require a technology to survive impacts. The pykrete ice shield I proposed could be much smaller, such as just one hexagonal hangar big enough for 2-3 starships in LEO at a time. Once refueled, the craft would go to the much safer L5 point or directly to the moon if that is the destination. Keeping a ring at L5 would not require a massive ice shield or centrifuge habitat to be a useful waystation. But those would be designed into it up front to give room for expansion.

If we decided that a Mars mission had to wait for all the infrastructure I proposed, we’d be in the same trap that Von Braun would have fell into of wanting massive infrastructure before the first crewed lunar mission. You need a balance of infrastructure and exploration to give both meaning.

“We can democratize early if we give some participation method in the initial investments in time, technology, and financing.”

SSP: Musk says he needs 100s of starships to deliver millions of tons of materials to support large cities on Mars by mid-century (his timeline). You’ve created a somewhat more reasonable timeline for Starship round trip logistics for this effort based on Hohmann transfer orbits and Mars orbital launch windows (i.e. every 2 years).

What will be the economic driver for such an ambitious project besides Musk just “making it so”? I saw later in your presentation that you proposed an initial sponsorship and collectables market followed by MarsSpec competitions. How will these initiatives kickstart sufficient market enthusiasm to support such an enormous fleet of Starships?

KN: It’s a complex topic, and easily a book in itself. To cut to the core of it, any major discovery or invention that is not democratized becomes historic or esoteric rather than revolutionary. Technology revolutions do not take place in particle accelerators any more than music revolutions take place in symphony orchestra pits. Things that don’t impact people constantly are simply curiosities. Even many things taken for granted like GPS and running water are ignored, but they remain transformative. When the furnace filter factory worker sends part of his month’s labor to Mars, we have space settlement. We can democratize early if we give some participation method in the initial investments in time, technology, and financing. But these waves will go from new and novel to basic and ignored rather quickly, and this is especially true if they succeed.

Imagine being a medieval merchant and getting an opportunity to send a bag of grain on a voyage to Cabot or some other explorer. In return you get a rock from the opposite side of the world, a certificate saying what you gave and authenticating what you got back, and a tiny bit of participation in the history of your era that you can share with your children. A decade later, your son is working in a smelting plant in a port city and making hardware for houses in the new world. In another decade your grandchildren are growing crops in Maryland. It’s a bit like that. Each wave will fund and create the industrial and skill base for the next wave before becoming culturally ubiquitous. The last child has no interest in a rock from his Maryland backyard. But to the grandfather living a generation or two beforehand, it may as well be from the moon. The wave of sponsorship, followed by specifications for space-rated products, followed by biological engineering in lower gravity worlds will each create benefits and enthusiasm back on Earth. After that last wave, the economic ecosystem becomes permanently multi-planetary.

Everything else about space is a simple engineering problem. Minds, trends, budgets, and so on are not so well behaved as atoms or heat, but they have a lot of history that we can use to model workable solutions. This is the one I came up with.

“The problem with any grand engineering venture is that every design looks good until it comes in contact with reality.”

SSP: The Eureka Space Settlement concept features dual centrifuges providing artificial gravity equivalent to the Moon and Mars.

I like the idea of using variable gravity to study biological effects on plant and mammalian physiology, adapting species to be multi-planetary and prepping for settlements that will need gravity as we move out into the outer solar system, but this can be done more cheaply in LEO or in cislunar space as outlined earlier in your architecture. Why not simplify the Eureka settlement by eliminating the centrifuge and going with normal Mars gravity?

KN: The problem with any grand engineering venture is that every design looks good until it comes in contact with reality. You can’t model every issue up front, and one of the hardest to work out without experience are multi-generational ecosystems. If we build a $100 billion Mars city and the kids have birth defects, we have a huge liability issue and a city that will be turned over to robots or dust.

The advocates assume all will be fine, but they tend to downplay issues. The critics assume all will go poorly, but they never want to venture past the status quo. Reality will be a mixed bag of data points on a bell curve between the two with both unknown threats and opportunities waiting for discovery. This unknown is a big reason for the enthusiasm to try in the first place.

I came up with the steelman methodology by taking all the criticisms and range of danger possibilities and cranking the bell curve values up a few sigma to the nasty side. The idea is that if you can STILL make an affordable design that pays for itself when the universe is coming after you with a hammer, you probably will be fine when the bell curve is realized. You should always have a back-down plan to have surface domes with no centrifuges, or simply use the centrifuges for pregnant mammals and trees that need to fight gravity to have enough limb strength to bear fruit. That said, another beauty of this design is that a Pluto colony or asteroid colony will almost certainly need centrifuges for multigenerational life. Prototyping it on Mars may be overkill for Mars, but perfect for Pluto or Enceladus. This makes it much easier for Mars settlers to think about colonizing the outer solar system. Even the children of our dreams need dreams, after all.

“A space outpost must bring materials to itself, so a system like that without surface outposts or asteroid mining is a dead end.”

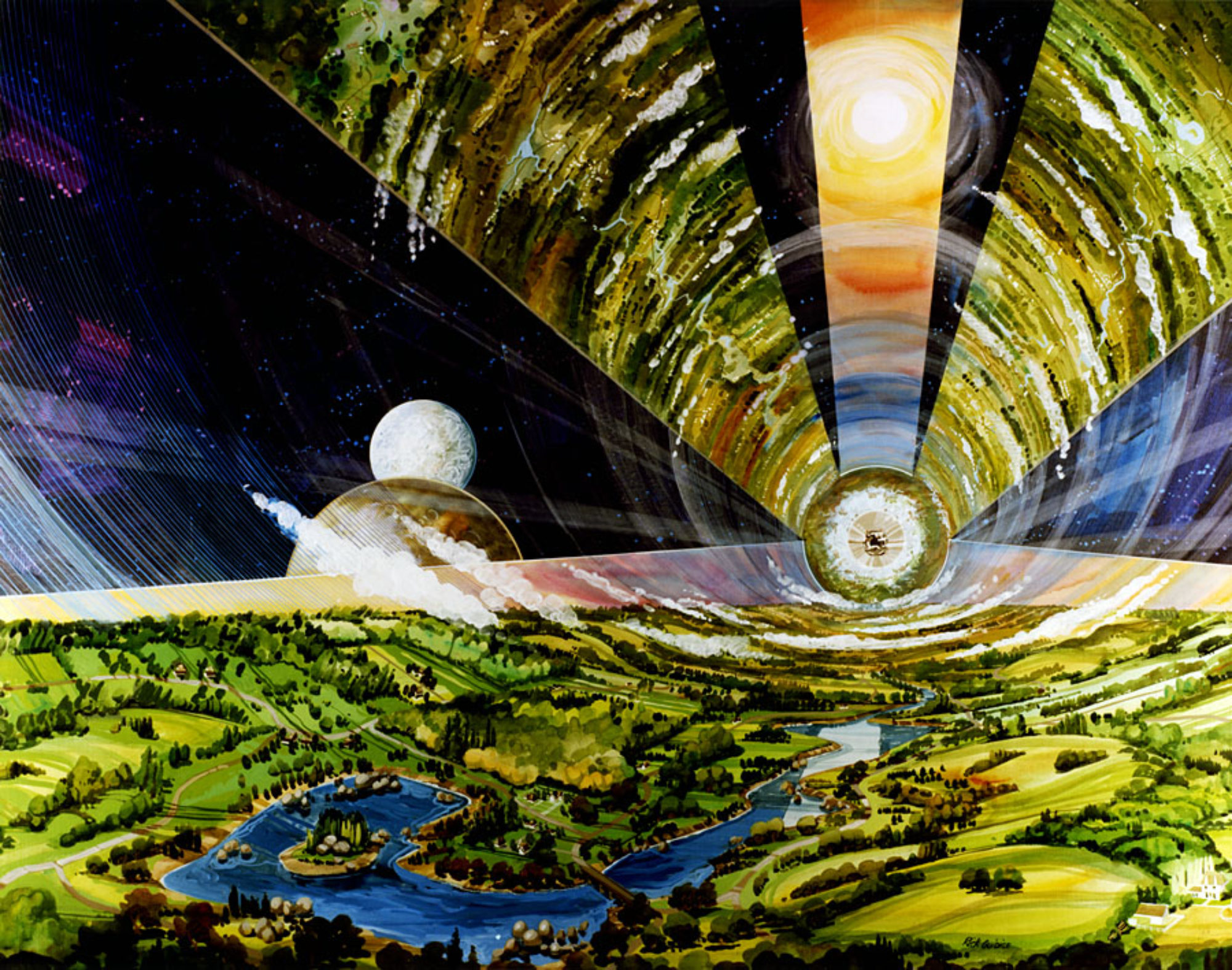

SSP: In the proposed first wave of the architecture, rotating settlements are created from Starship building blocks in high orbit to create “…deep space industrial outposts in the O’Neill tradition with a thousand inhabitants each. On the lunar and Martian surface, we simply take a slice of the ring architecture with starships inside as an outpost.” With the amount of investment needed to build the infrastructure to transport materials and people for large settlements on Mars, and given that the biggest grand challenge on your chart is reproduction (which may not be possible in less than Earth’s gravity), why wouldn’t it make more sense to focus efforts on building larger 1G rotating free space settlements where we know having children is possible?

KN: It’s not so much a roadmap of first this structure here, then that one there. It’s a draft set of compatible building standards for everywhere. Think about the standard sizes for bricks, pipes, and wiring and how entire continents use them interchangeably over a hundred years or more. My goal was to lay out what the maximum amount of infrastructure would look like with the minimum number of parts.

There is a false dichotomy between structures like space stations made entirely from material from Earth, and local materials formed with 3D printers that can do everything with complete reliability. Both are impractical extremes, and to some degree strawman designs. Importing everything is prohibitively expensive even with Starship. Conversely, creating structures from random conglomerates of whatever material is at the landing site will be too brittle. By proposing bags that can be made of basalt cloth but that will initially come from Earth, I’m bridging the two extremes. They can be filled with dust, water, sand, or whatever is fine grained enough and can be either sintered or cemented in place. Such structures don’t have to be aligned with absolute precision and can follow soft contours or whatever is needed. You also don’t need four meters of shielding for cosmic rays if you augment it with magnets. They can be scaled in layers or levels as needed, just like bricks or two by four boards are in homes.

A space outpost must bring materials to itself, so a system like that without surface outposts or asteroid mining is a dead end.

Centrifuges for surface settlements are a bit awkward, to be sure. A train system that keeps the floor below you when spinning or de-spinning is a better system at first. Eureka was mainly done with fixed pitch decks just to show that the scale of a centrifuge for a large torus L5 ring could be done on a surface with some clever engineering. My original design goal was to make the cars, car beds, rails, and buildings swappable without stopping the ring rotation. In the same way, the pressure shell has inner and outer walls that can in theory be replaced while the other keeps pressure. It’s probably not necessary, but the goal is to remove all design barriers early in the thought process so that future engineers aren’t painted into corners.

SSP: After the first settlements are established on Mars, you suggest starting to adapt the Mars environment to Earth-like conditions through “para-terraforming” small parts of the planet such as the Hebes Chasma, a canyon the size of Lake Erie just north of Valles Marineris. This feature has the advantage of being right on the equator and closed at both ends so that kilometer sized arch structures could enclose the valley to warm the local environment with many Eureka settlements below.

Planetary protection was mentioned as one of the grand challenges to be overcome. Some space scientists are advocating for robotic missions to answer the question of whether life existed (or still exists) on Mars before humans reach Mars. No such missions are planned prior to Musk’s timeline for putting humans on Mars at the end of this decade. Are you assuming that by the time humans are ready for para-terraforming that the question of life on Mars will be answered?

KN: We would certainly know if active, widespread, indigenous life was an issue by the time of building canyon settlements the size of Lake Erie. Even isolated pockets would leave fossil traces in broader zones.

The bigger question is that of whether or not it is possible to settle Mars if there is a risk of crossing into a local biome accidently. Eureka is built entirely on the surface, so it doesn’t cross the sterilized surface soils if it doesn’t have to. We should be able to mine from Mars with sterile equipment and be able to sterilize further after robotic extraction. We can extract water ice, volcanic rock, and surface dust and build the entire settlement from those basic materials. We can avoid sedimentary materials until we are confident they are not biologically active.

I suspect any life on Mars is from Earth, and brought by meteors. The cross-traffic of meteors throughout the solar system may mean bacterial and possibly slightly more complex life all over the solar system from the late bombardments of Earth. We should consider this no more exotic than breathing in Australia or swimming in the ocean. Microbes adapted for those environments would not be adapted to be pathogenic because why spend billions of generations preparing for a food source that may never arrive? We would have a bigger problem with random toxins that hadn’t leached out or reacted to life billions of years ago than with life itself. I respect the work of those who want sterile capsules of pristine soil captured by the current Mars rover prior to human arrival. That certainly makes sense. I like Carol Stoker’s Icebreaker mission concept. I think NASA and universities would be smart to work with SpaceX on simple rack-mount instrumentation that could be flown to planetary destinations en masse and serviced by Optimus Prime Tesla robots.

“My goal is to build the next generation of the quiet heroes of the dinner table. And certainly a few of those will be leaders too.”

SSP: You’re writing a book about creating an inventor mindset to enable a million “mini-Musks” – people who are not necessarily rich, but who shake up the world in constructive and innovative ways. Tell us more about this philosophy.

KN: The core concept is that if you could get a thousand people to do a hundredth of what Elon has accomplished, it would be a tenfold increase in what we’ve seen in terms of his contribution to technology. That’s not a very big ask individually, even if it’s more garage labs than factories for now. I looked deeply into what Elon Musk does and what other inventors like him have done. I’ve looked at technology revolutions and what key things spark the massive growth waves of innovation. Obviously, there are intersections between the two.

I’m writing a short book this summer to document Elon’s methodologies in an approachable and comprehensive reference. If it attracts enough interest, I can take that core module into different directions. One is digging more into how the mind invents. Another is breaking down how technology revolutions work. A third is all this work on space settlement. I’ve also come up with intellectual property around the root of these concepts that would be valuable software and services. I guess we’ll see what reaction the Elon book gets and see where that goes. It’s a bit heartbreaking to see millions spent on NFTs and other random “stupid money” projects when I’m coming up with concepts for trillion-dollar companies as a hobby.

While we talk a lot about Musk, there are thousands of people who work just behind the spotlight. My father was a production test pilot who put his life on the line to ensure that bombers were flyable for national security, and that the technology that became the commercial jet airliner a decade later would be safe for billions of travelers. He worked with some historic figures of aviation, and his dinner stories were amazing. The Mars Society gave me a way to repeat a little of this history for myself in this dawn of the Mars Age.

Technology revolutions may celebrate a few leaders. But without thousands of talented people several feet behind these inventors, they are little more than curiosities – Di Vinci notebooks or Antikythera mechanisms. My goal is to build the next generation of the quiet heroes of the dinner table. And certainly a few of those will be leaders too. That is my hope. To fill the diaries of pioneers that give permanent cultural bedrock to the accomplishments of people like Elon. Otherwise, even a moon landing is a short story written in water.

Don’t miss Kent’s appearance on The Space Show coming up on Sunday July 10 where you can call in and ask him in person your own questions about these and other visions for space settlement.