Last April, an international team of researchers published a green paper to solicit public consultation on the urgent need for dialogue concerning uncontrolled human conception which will be problematic for space tourism when it takes off in the near future. A coauthor on the paper, Alex Layendecker of the Florida based Astrosexological Research Institute (ASRI) studied the subject for his PhD thesis. Layendecker gave a talk at ISDC 2023 entitled Sex in Space in the Era of Space Tourism in which he emphasized the huge knowledge gap we have on mammalian conception, gestation and birth in the high radiation and lower gravity environments of outer space. Since humans evolved for millions of years in Earth’s gravity protected from radiation by our planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere, there is a significant risk of developmental abnormalities in offspring which could result in legal liability and potential impacts on commerce if conception occurs in space without consideration of the potential hazards. After his talk, I discussed these matters and the implications for space settlement with Alex who agreed to continue our discussion in an interview by email for this post.

SSP: Alex, it was a pleasure meeting you at ISDC and thank you for taking the time to answer my questions on this important topic. The green paper is attempting to foster discussion from relevant stakeholders on addressing “uncontrolled human conception”. Uncontrolled is defined in the paper as “…without societal approval for human conception – i.e. without regulatory approval from relevant bodies representing a broad societal consensus.” I am not aware of any regulatory authority on these matters at this time and there will likely be considerable challenges to obtain consensus across the space community before tourism becomes mainstream. The intent of the paper appears to be to help develop a framework for regulations (or guidelines) before space tourism takes off. Given how long it takes for regulations to be implemented and the challenges of international consensus, will there be enough time to implement sufficient controls before conception happens in space?

AL: Great question – short answer up front, no, I don’t believe any “controls” will be implemented before the first incidence of human conception in space, given the timelines we’re currently looking at. As you mentioned, regulations can take a long time to come into effect and you need to have a basis for establishing regulations/law – space law itself is still being developed. Our knowledge of reproduction in space is minimal at this stage, certainly not at the level it needs to be at this point of history. We’re also in virtually unexplored territory when it comes to mass space tourism – there have been space tourists in the past, Dennis Tito being the first “official” space tourist in history over 20 years ago – but all previous individuals that went into space for tourism purposes have done so while integrated into the crew, typically with very little privacy and a considerable amount of training. With mass access to space, we’ll soon have groups of individuals going up solely for vacation/leisure purposes, and you can be assured some of them will be engaging in sexual activity. While it would be absurd to try to implement or enforce laws preventing sexual activity in those environments, the dangers associated with potential conception still exist. What is critically needed at this point is a better collective understanding of those dangers, their mitigation, and for space companies to be able to provide those paying customers with enough information that informed consent can be established – space is inherently dangerous already, and people launching into space are briefed on that. They will need to be briefed on the dangers associated with conception in space as well, which could not only potentially threaten the life of the baby but also that of the mother, depending on the times and distances involved.

SSP: Will this be a government effort (since a green paper typically implies government sponsorship) or a self-imposed industry-wide trade association consensus approach like CONFERS? Or a combination?

AL: I think in the immediate sense, there will need to be a self-imposed industry consensus on establishing informed consent among space tourism customers. Sex and potential conception in space is currently a blind spot for would-be space tourism companies, because up to this point many of them haven’t considered the dangers it could pose to their customers, and corporate liability here is also an issue. It’s their responsibility to keep their passengers safe, and to inform them of any dangers to the max extent possible. I don’t necessarily see governments being able to implement or enforce any regulations in this regard, because regulating people doing what they want with their own bodies in the privacy of their own bedrooms typically doesn’t fare well over the long term. Where governments may get involved is if any medical situation develops to the point of needing rapid rescue, but Space Rescue capabilities is another topic.

SSP: Space tourism is likely to attract thrill seekers and risk-takers who are likely to have rebellious personalities with a reluctance to follow rules and regulations, let alone respect for societal norms. If this is the case, will pre-flight consultations on the risks of uncontrolled conception and legal waivers be sufficient to prevent risky behavior? Can the effectiveness of this approach be tested prior to implementation?

AL: Prevent risky behavior? Absolutely not. As you point out, these are folks who are intentionally undertaking an enormously risky endeavor in flying to space already, and at least in the early years, will be primarily comprised of your limits-pushing, boundary-breaking types. So they’re already about risk as individuals. However, legal waivers will of course be part of the whole operation, likely to include waivers around the risks of conception. Waivers or not, people are still going to engage in sex in space, and relatively soon, and if the individuals in question are capable of conception, the act itself brings that risk. Not to mention that there are individuals out there who will be vying for the title of “first couple to officially have sex in space,” despite speculation over the years that it could have occurred in the past. To be part of the first publicly declared coupling in outer space will land their names in history books. Now, there will be individuals who decide that they don’t want to deal with those risks after a thorough briefing on the potential dangers, but not everyone – probably not even a majority, knowing humans – will be deterred.

SSP: The paper highlights concerns about pregnancy in higher radiation and microgravity environments. From a space settlement perspective, radiation is less of a problem as there are engineering solutions (i.e. provision for adequate shielding) to address that issue. The bigger challenge will be pregnancies in microgravity, or in lower gravity on the Moon and Mars. The physiology of human fetus development in less than 1g is a big unknown. Some space advocates such as Robert Zubrin brush this off with the logic that a fetus in vivo on Earth is developing in essentially neutral buoyancy, and is therefore weightless anyway, so gestation in less than 1g probably won’t matter. Setting aside the issues associated with conception in lower gravity, if a woman can become pregnant in space, do you think this logic may be true for gestation or are there scientific studies and/or physiological arguments on the importance of Earth’s gravity in fetal development that refute this position?

AL: I’ve heard the neutral buoyancy argument before but it doesn’t address all the issues by a long shot. There is more neutral buoyancy during the first trimester of gestation but in the second and third gravity is very important, even just logistically speaking. Gravity helps the baby orient properly for delivery, and helps keep the mother’s uterine muscles strong enough to provide the necessary level of contractions to safely move the baby through the birth canal. On a more cellular level, cytoskeletal development is impacted by gravity, so even proper formation and organization of cells can be affected by microgravity throughout the span of gestation, from conception to birth. Gravity has a huge impact on postnatal development as well – in the small handful of NASA experiments we’ve conducted using mammalian young (baby rat and mouse pups), there were significant fatality rates among younger/less developed pups against ground control groups when exposed to microgravity during key postnatal phases. The youngest pups (5 days old) suffered a 90% mortality rate, and any of the survivors had significant developmental issues. So gravity is crucial not just to fetal development but to newborns and children as well, that much is evident from the data we do have.

SSP: Following up on your response, the Moon/Mars settlement advocates will say partial gravity levels on these worlds may be sufficiently higher than in microgravity to address the issues you mentioned – baby orientation, cytoskeletal development, cellular formation/organization, postnatal development – and a full 1g may not be needed for healthy reproduction. The mammalian studies you mentioned with detrimental postnatal development were in microgravity. We now have a data point at the lunar gravity level from JAXA with their long awaited results of a 2019 study on postnatal mice subjected to 1/6g partial gravity in a paper in Nature that was published last April. The good news is that 1/6g partial gravity prevents muscle atrophy in mice. The downside is that this level of artificial gravity cannot prevent changes in muscle fiber (myofiber) and gene modification induced by microgravity. There appears to be a threshold between 1/6g and Earth-normal gravity, yet to be determined, for skeletal muscle adaptation. Have you seen these results, can you comment on them and do you think they may rule out mammalian postnatal development in lunar gravity?

AL: With regard to the JAXA study, I think I’ve seen a short summary of preliminary results but haven’t gotten to read the full study yet. What I will comment for now is that there’s at least some promise in those results from a thousand foot view. While we still need to determine/set parameters for what we as a society/species consider medically/ethically acceptable for level of impact (obviously there was gene modification in the JAXA mice), there are clearly still some benefits to even lower levels of gravity.

SSP: With respect to risk mitigation and the paper’s recommended area of research: “Consolidation of existing knowledge about the early stages of human (and mammalian) reproduction in space environments and consideration of the ensuing risks to human progeny”, SSP has covered off-Earth reproduction and highlighted the need for ethical clinical studies in LEO to determine the gravity prescription (GRx) for mammalian (and eventually human) procreation. During our personal discussions at ISDC, you mentioned ASRI’s plans for such studies in space. Can you elaborate on your vision for mammalian reproduction studies in variable gravity? What would be your experimental design and proposed timeline?

AL: Well, with regard to timelines, humanity as a whole is already behind, so we’ll need to move as quickly as we possibly can while still upholding safe medical and ethical standards. We’re approaching an inflection point where human conception in space is more probable to occur, and we still have vast data gaps that need to be filled on biological reproduction. I’d advocate that the best way to go about filling those gaps would be a systematic approach using mammalian test subjects to determine safe and ethically acceptable gravity parameters for reproduction. We already know a decent amount about the impacts of higher radiation levels on reproduction from data gathered on Earth, but with microgravity we’ve still got a long way to go, and we don’t know what the synergistic effects of microgravity and radiation are together either. With regard to experiments, NASA researchers have actually already designed extensive mammalian reproduction experiments with university partners, but those experiments haven’t been funded by the agency. There was a comprehensive experiment platform called MICEHAB (Multigenerational Independent Colony for Extraterrestrial Habitation, Autonomy and Behavior) that was proposed back in 2015, around the time I was completing my PhD dissertation. It would effectively be a robot-maintained mini space station that would study the microgravity and radiation effects on rodents in spaceflight over multiple generations, which of course requires sexual reproduction. That experiment alone would prove enormously beneficial to data collection efforts. It would be important to study said generations and physiological impacts at variable gravity levels as you mentioned – think the Moon, Mars, 0.5 Earth G, 0.75 Earth G and so on, so we could fine tune what level of impact we as a species are medically and ethically willing to accept in order to settle new worlds. With regard to ASRI’s experiment roadmap, our intent is to start with smaller, simpler experiments that will garner us more data on individual stages of reproduction first using live mice and rats, with the hope of eventually moving on to complex and comprehensive experiments like MICEHAB. Once we have a good plot of data over the course of many experiments, we can hopefully move on to primate relative studies to establish safe parameters for human trials. I anticipate the small mammal experiments alone will take at least five years were we to launch our first mission at this very moment – though speed is often dependent on level of funding, as happens with most science.

SSP: If contraceptives are recommended to prevent conception during space tourism voyages, the paper calls for validation of the efficacy of these methods in off-world environments. Do your plans for variable gravity experiments include such studies and how would you design the protocol?

AL: Well, the first important thing to remember is that contraceptives are known to fail occasionally on Earth – condoms can break (especially if used incorrectly), and even orally-taken birth control pills aren’t considered 100% effective. Currently ASRI doesn’t have plans for contraception studies because that’s further forward than we can reasonably forecast at this point. Frankly we need to establish medical parameters first regarding conception in space and know where the risk lines are before we implement birth control studies using humans. We have to take many small steps before we get there. Once we do have established limits for safe reproduction in space environments, we would look to operate any birth control studies within those parameters to determine efficacy. That way if the contraceptives do fail, we at least know the resulting pregnancy has a reasonable chance of success.

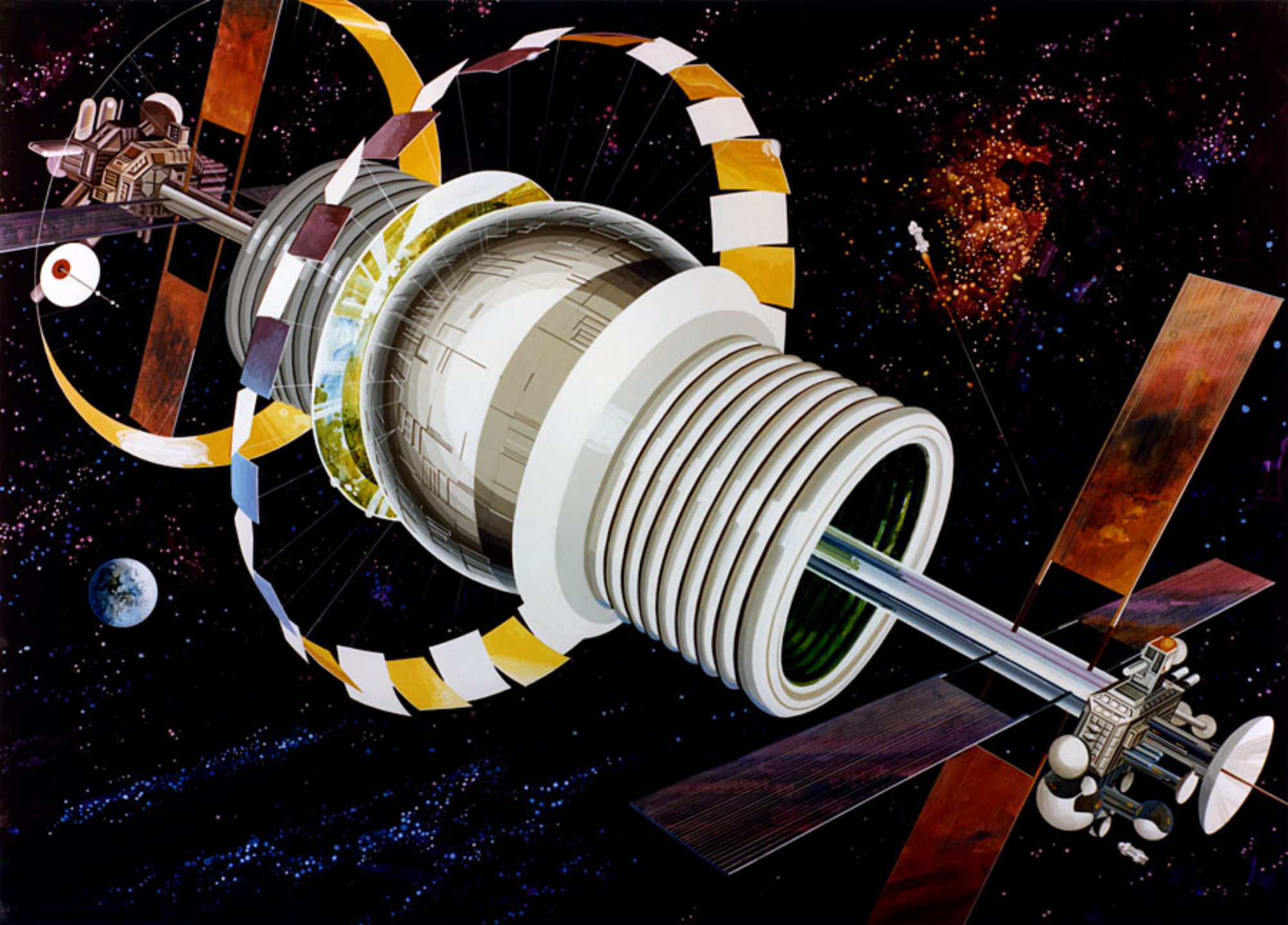

SSP: Should experiments on mammalian reproduction in variable gravity determine that fetal developmental or health issues arise after conception and gestation in less than 1g, do you think this may lead to a significant shift in the long-term strategy for space settlement (e.g. toward O’Neill type artificial gravity space settlements) if children are to be born and raised in space?

AL: I certainly think so. There’s a lot at stake here. If we can’t safely birth and grow new generations of humans at a Martian gravity level (0.38 Earth G), then we’ve largely lost Mars as a destination for permanent multigenerational settlement. Fully grown adults can live and work down on the planet itself, but we’d need to come up with an alternate nearby solution for pregnant mothers and children growing up to certain age. From an engineering perspective, artificial gravity space settlements like an O’Neill cylinder make the most sense to me personally, so long as there’s Earth-level radiation shielding and gravity, and you can recreate Earth-like environments within those structures. During our conversation at ISDC I referred to it as an “Orbital Incubator” concept, though I’m of course not the first person to ever discuss something like that.

SSP: I appreciate you sharing your PhD Thesis with me. In that work you developed the Reproduction and Development in Off-Earth Environments (RADIO-EE) Scale to provide a metric that could help future researchers identify potential issues/threats to human reproduction in space environments, i.e. microgravity and radiation. Respecting your request that the images of the metric not be published at this time, qualitatively, the scale plots the different phases of reproduction, fetal development, live birth and beyond against levels of gravity or radiation in outer space environments encompassing the range from microgravity all the way up to 1g (and even higher). The scale displays green, amber, and red areas mapping safe, cautionary, and forbidden zones, respectively, dependent on location (e.g. Moon, Mars, free space, etc.). When I originally read your thesis I thought you included both gravity and radiation on the same chart but after our discussions I understand that they would have to be separated out. I also acknowledge that we have no data at this time and the metric is a work in process to be filled in as experiments are performed in space. Have you considered using three dimensions (gravity on x-axis, radiation on the y-axis, viability on the z-axis) and create a surface function for viability. Does that make sense?

AL: I’m totally with you on the 3D model scale (I’ve always thought of it like navigating a “tunnel” made up of green data points to reach the end of the reproductive cycle safely). The scale was originally envisioned as separate graphs for Microgravity/Hypergravity and Radiation, but obviously we couldn’t combine those in 2D because those two different factors can vary wildly depending on where you’re physically located in the solar system/outer space in general. So the best answer is to effectively plot green, amber, and red “zones” on each chart (again based on location), then make sure that wherever we’re trying to grow/raise offspring (of any Earth species) we’re keeping our expectant mothers and children in double-green zones (for both gravity, and radiation). Now the third axis would actually be time (i.e. what point are you at in the reproductive cycle), with viability being determined by where all three axes meet in a green/amber/red zone.

I’d like to thank Alex for this informative discussion and look forward to further updates as his research progresses. We urgently need his insights to inform ethical policies and practices regarding reproduction for the space tourism industry in the short term, and eventually for having and raising healthy children wherever we decide to establish space settlements. Readers can listen to Alex describe his research live and talk to him in person when he appears on The Space Show currently scheduled for August 27.