Earlier this year SSP covered self replicating factories for space settlement. An innovative paper on this topic with a simpler approach was submitted by Mikhail Shubov to ArXiv.org in August that shows how to accelerate efforts in this area.

A fully autonomous self replicating factory in space requires significant advancements in artificial intelligence, robotics, and other fields. Such facilities are mainly theoretical at this point and may not be feasible for many decades. But if humans could “guide” the operation remotely via computer control, a colony on the Moon could be started relatively soon. This could be the proving ground for establishing such facilities on other worlds which Shubov believes could be set up on Mercury, Mars and in the Asteroid Belt eventually leading to exponential growth allowing humanity to expand out into the solar system and beyond. He suggests that rather then using the usual definition of self-replication in which a factory would make a duplicate copy of itself, until this capability is realized, a better figure of merit would be the “doubling time”. This is how long it takes to double the facility’s mass, energy production, and machine production.

I reached out to Dr. Shubov about this article and discovered that he has been busy with a variety of scholarly papers on several technologies needed for space settlement. He agreed to a wide ranging interview via email about these topics and his vision of our future in space.

SSP: Thank you Dr. Shubov for taking the time for this interview. With respect to your work on Guided Self Replicating Factories (GSRF), there are already companies developing semiautonomous robots for in situ resource utilization on other worlds. OffWorld, Inc. states that “We envision millions of smart robots working under human supervision on and offworld, turning the inner solar system into a better, gentler, greener place for life and civilization.” Their business model is focused on developing a robotics platform for mining and construction on Earth, then leveraging the technology for use in space. Do you think this is a good approach to get started?

MS: Thank you Mr. John Jossy for taking interest in my work!

In my opinion, remotely guided robots will be very effective for construction of a colony on the Moon. These robots could be guided by thousands of remote operators on Earth. They would be linked to Earth’s Internet via Starlink which is already being deployed by Elon Musk via SpaceX. Starlink will consist of thousands of satellites linked by lasers and providing broadband Internet on Earth. About 1,646 satellites are already orbiting the Earth.

Hopefully, it would be possible to produce [an] Earth-Moon Internet Connection of about a Terabit per second. That would enable people on Earth to remotely operate hundreds of thousands of robots.

Using these robots on Asteroids and other planets of Solar System will be much more difficult due to low bandwidth and high delay of communication. For example, latency of communication between Earth and Mars is 4 to 21 minutes.

SSP: Obviously, establishing outposts on other worlds where astronauts could teleoperate robots to build a GSRF would eliminate the latency problem, which you address in your paper.

You’ve envisioned four elements of a GSRF: an electric power plant, a material production system (ore mining, beneficiation, smelting), an assembly system in which factory parts are shaped and fabricated, and a space transportation system. With respect to the space transportation system you cover both launch vehicles and in-space propulsion systems. The space transportation element of a GSRF, although vital for its implementation, seems to be an external part of the system. In fact, you stated that “Initially, spaceships will be built on Earth. Fuel for refueling spaceships will be produced in space colonies from the beginning.” So, when calculating the doubling time of a GSRF, we are not including the production of space transportation systems, correct?

MS: In my opinion, [the] space transportation system may become part of GSRF at later stages of development. How soon space transportation becomes a part of GSRF depends on the speed of development of different technologies.

If inexpensive space launch from Earth becomes available, then there will be less reliance on self-replication and more reliance on transportation of materials from Earth. In this case, space transportation system will not be part of GSRF for a long time.

If rapid growth of a Space Colony by utilization of in situ resources is possible, then many elements of space transportation system would be produced at the colony. In this case, [the] space transportation system will become a part of GSRF relatively soon.

SSP: You suggest that an important product produced by a GSRF in the Asteroid Belt would be platinum group metals to be delivered to Earth, and that they would help finance expansion of space colonization. Some space resource experts, including John C. Lewis, believe that “…there is so vast a supply of platinum-group elements in the NEA [Near Earth Asteroids] … that exploiting even a tiny fraction of them would cause the market value to crash, bringing to an end the economic incentive to mine and import them.” Some suggest the market for these precious metals may be in space not on Earth. When you say “delivered to Earth” what markets were you envisioning to generate the profits needed to finance the GSRF?

MS: In my opinion the main applications of platinum group metals would be in industry. First, PGM are very important as chemical reaction catalysts. In particular, platinum is used in hydrogen fuel cells and iridium is a catalyst in electrolytic cells. It is likely that demand for platinum, iridium and other PGM will grow along with hydrogen economy. Second, platinum and palladium is used in glass fiber production.

Third, Iridium-coated rhenium rocket thrusters have outstanding performance and reusability. Rhenium is also used in jet engines. These thrusters will also provide a market for iridium and rhenium metals.

SSP: As the need for PGM grows exponentially in the future, especially with energy and battery production needs on Earth in the near future, the environmental impacts of mining these materials on Earth may be another reason to source these materials off world.

Mining water to produce hydrogen for rocket fuel is a theme throughout your writings. In a paper submitted to the arXix.org server last month entitled Feasibility Study For Hydrogen Producing Colony on Mars, you propose that a technologically mature Martian factory could produce and deliver at least 1 million tons of liquid hydrogen per year to Low Earth Orbit. Does placing a hydrogen production facility on Mars for fuel used in near-Earth space make sense from a delta-v perspective? You acknowledge that initially it will be cheaper and easier to access the Moon’s polar ice to produce hydrogen. But in the long term, Near Earth Asteroids (NEA) or even the Asteroid Belt are easier to access and they include CI Group carbonaceous chondrites which contain a high percentage (22%) of water. Can you reconcile the economics of sourcing hydrogen on Mars over NEAs?

MS: Delivery of Martian hydrogen into the vicinity of Earth may be necessary only when the space transportation technology is relatively mature. In particular, as I mention in my work, Lunar ice caps contain between 48 million and 73 million tons of easily accessible hydrogen. Until at least 16 million tons of Lunar hydrogen is used, hydrogen from other sources would not be needed.

As I calculate in my work, delta-v for transporting hydrogen from Low Mars Orbit to LEO is 3.5 km/s accomplished by rocket engines plus about 3.2 km/s accomplished by aerobreaking. This would be economic if vast amounts of electric energy will be produced on Mars easier than on asteroids. An important and renewable resource on Mars is the heat sink in the form of dry ice. This may enable production of vast amounts of electric energy by nuclear power plants.

Even if delivery of hydrogen from Low Mars Orbit to Earth turns out to be economically infeasible, hydrogen depots in near-Mars deep space would still play a very important role in transportation to and from Asteroid Belt as well as [the] Outer Solar System.

SSP: Your first choice of a power source for the colony on Mars is an innovative heat engine utilizing dry ice harvested from the vast cold reservoirs at the planet’s polar caps. You suggest that the initial heat source for this sublimation engine be a nuclear reactor. Why not simply use the nuclear reactor to produce electricity? Nuclear reactors coupled to high efficiency Stirling engines for electricity generation like NASA’s Kilopower project have very high power density per unit weight and the technology will be relatively mature soon. Your second choices are solar and wind which are not as reliable as a nuclear power source, especially with reduced solar flux at Mars’s orbit and the problem caused by dust in the atmosphere. Why was a more mature nuclear power technology for direct electricity production not considered?

MS: Thank you. As I understand now, a regular nuclear reactor with a heat engine using water or ammonia as a working fluid is the best choice for energy production on Mars. Dry ice should only be used as a heat sink and not as working fluid. Given the very low temperature and ambient pressure of Martian dry ice, it is likely that power plants will have thermal efficiency of at least 50%.

Almost all components of Martian power stations can be manufactured from in situ resources. Only the reactors themselves and the nuclear fuel will have to be delivered from Earth.

SSP: A booming space transportation economy will need cryogenic fuel depots to store hydrogen for rocket fuel in strategic locations throughout the inner solar system. You’ve got this covered in your recent paper Hydrogen Fuel Depot in Space. Some start ups like Orbit Fab have already started work in this area, albeit on a smaller scale, and United Launch Alliance integrated cryogenic storage into their Cislunar-1000 plans a few years back, but this initiative seems to have slowed down due to delays in ULA’s next generation Vulcan launch vehicle. In this paper you calculate the required energy to refrigerate hydrogen in one smaller (400 tons) and another larger (40,000 tons) depot. In both cases, a sun shield is required to block sunlight to prevent boil off. You don’t mention the method of power generation to provide energy for the refrigeration units. Could the sun shield have a dual use function by incorporating photovoltaic solar cells on the sun facing side to generate electricity to power the refrigeration system?

MS: Power for the refrigeration system will be provided by an array of solar cells placed on the sun shield. As I mention in my work, the 400 ton depot requires 80 kW electric power for the refrigeration system, while the 40,000 ton depot requires 840 kW electric power. This power can be easily provided by photovoltaic arrays.

SSP: SpaceX has proven what was once believed impossible: that rockets could be reused and that turnaround times and reliability could approach airline type operations. Although we are not there yet, costs continue to come down. In your paper entitled Feasibility Study For Multiply Reusable Space Launch System you calculate that with your proposed system in which the first two stages are reusable and the third stage engine can be returned from orbit, launch costs could be reduced to $300/kg. Musk is claiming that with the projected long term flight cadence, eventually Starship costs could be as low as $10/kg. Even if he is off by a factor of 10 that is still lower than your figure. What advantages does your system offer over Starship?

MS: The main advantage of the Multiply Reusable Space Launch System is the relatively light load placed on each stage. As I mention on p. 10, the first stage has delta-v of 2.6 km/s and the second stage has delta-v of 1.85 km/s. The engines have high fuel to oxidizer ratio and a low combustion chamber temperature of 2,100oC. These relatively light loads on the rocket airframes and engines should make these rockets multiply reusable similar to airliners. The launch system should be able to perform about 300 space deliveries per year.

Hopefully Elon Musk would succeed [in] reducing launch costs to at least $100 per kg. Unfortunately, many previous attempts at drastic reduction of launch costs did not succeed. Hence, we may not be sure of Starship’s success yet.

SSP: You state in several of your papers that:

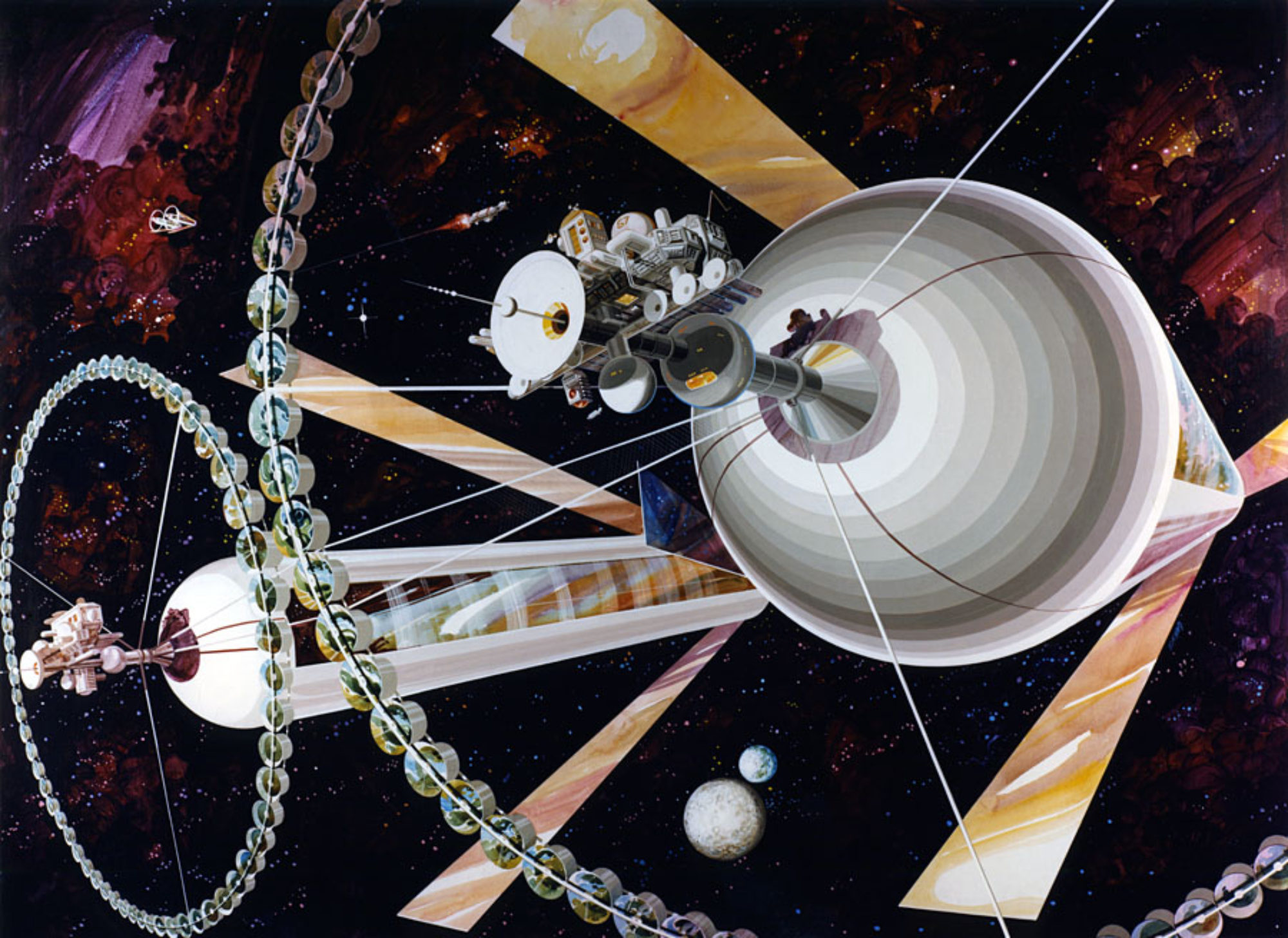

“A civilization encompassing the whole Solar System would be able to support a population of 10 quadrillion people at material living standards vastly superior to those in USA 2020. Colonization of the Solar System will be an extraordinary important step for Humankind.”

Why do you think that colonization of the solar system is important for humanity and when do you think the first permanent settlement will be established on the Moon or in free space? Here I use the National Space Society’s definition of a space settlement:

‘ “A space settlement” refers to a habitation in space or on a celestial body where families live on a permanent basis, and that engages in commercial activity which enables the settlement to grow over time, with the goal of becoming economically and biologically self-sustaining as a part of a larger network of space settlements. “Space settlement” refers to the creation of that larger network of space settlements. ‘

MS: In my opinion colonization of Solar System will bring unlimited resources and material prosperity to Humankind. The human population itself will be able to grow by the factor of a million without putting a strain on the available resources.

As for the time-frame of establishment of human settlements on the Moon and outer space, I have both optimistic and pessimistic thoughts. On one hand, Humankind already possesses technology needed to establish rapidly growing space settlements. This means that Solar System colonization can start at any time. On the other hand, such technology already existed in 1970s. This technology is discussed in Gerard K. O’Neill’s 1976 book “The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space”. Thus, space colonization can be indefinitely delayed by the lack of political will. Hopefully space colonization will start sooner rather then later.