The economics of an in-space industry based on lunar-derived rocket propellant was examined by Florida Space Institute planetary physicist Philip Metzger in a prepublication paper submitted to arXiv on March 16 . The study will be published in the June issue of Acta Astronautica. Many skeptics of this approach believe that with launch costs plummeting, driven down primarily due to reusability pioneered by SpaceX, it will be cheaper to power the nascent cislunar economy with propellant launched from Earth rather then fuel derived from lunar ice mining.

In his analysis, Metzger examines a cislunar economy of companies that operate geostationary satellites which need to purchase boost services using orbital transfer vehicles fueled by cryogenic hydrogen and oxygen. The question is, would sourcing H2/O2 from ice mined on the Moon be competitive with launching propellant from Earth. He notes that previous studies that favored Earth to solve this problem were flawed because they compared the different technologies for mining water on the Moon (e.g. strip mining, borehole sublimation, tent sublimation, or excavation with beneficiation) rather than analyzing the economics of the cis-lunar economy as a sector.

With that approach in mind, Metzger develops an economic model with figures of merit to assess how various technologies for ice mining compare to Earth sourced propellant. One such parameter is the “gear ratio” G, which in the parlance of orbital dynamics, is the ratio of the mass of hardware and propellant before versus after moving between two locations in accordance with the rocket equation. The other key metric is the production mass ratio Ø, which is the mass of propellant delivered to a specific location divided by the mass of the capital equipment needed to produce the fuel.

The “tent sublimation technology” mentioned in the paper was invented by George Sowers and is featured in his 2019 NIAC Phase I Final Report on ice mining from cold bodies in the solar system covered by SSP previously.

Although G is constrained by the laws of physics, reasonable values are possible and a value of Ø ≥ 35 is the threshold above which lunar propellant wins out. The tent sublimation technology is estimated to have Ø over 400, an order of magnitude higher than the minimum to gain an advantage. Metzger’s new approach took into account that launch costs will eventually come down as far as possible but even then, found that lunar propellant can be produced at a competitive advantage. The only caveat is validation of the TRL and reliability of ice mining technologies.

“Lunar-derived rocket propellant can outcompete rocket propellant launched from Earth, no matter how low launch costs go.”

Although not included in Metzger’s study, a method for extraction of water from lunar regolith is heating by low power microwaves. A recent study found that this technology is effective for extracting water from simulated lunar soil laced with ice. It would be interesting to see if Ø for this technique exceeds the advantage threshold.

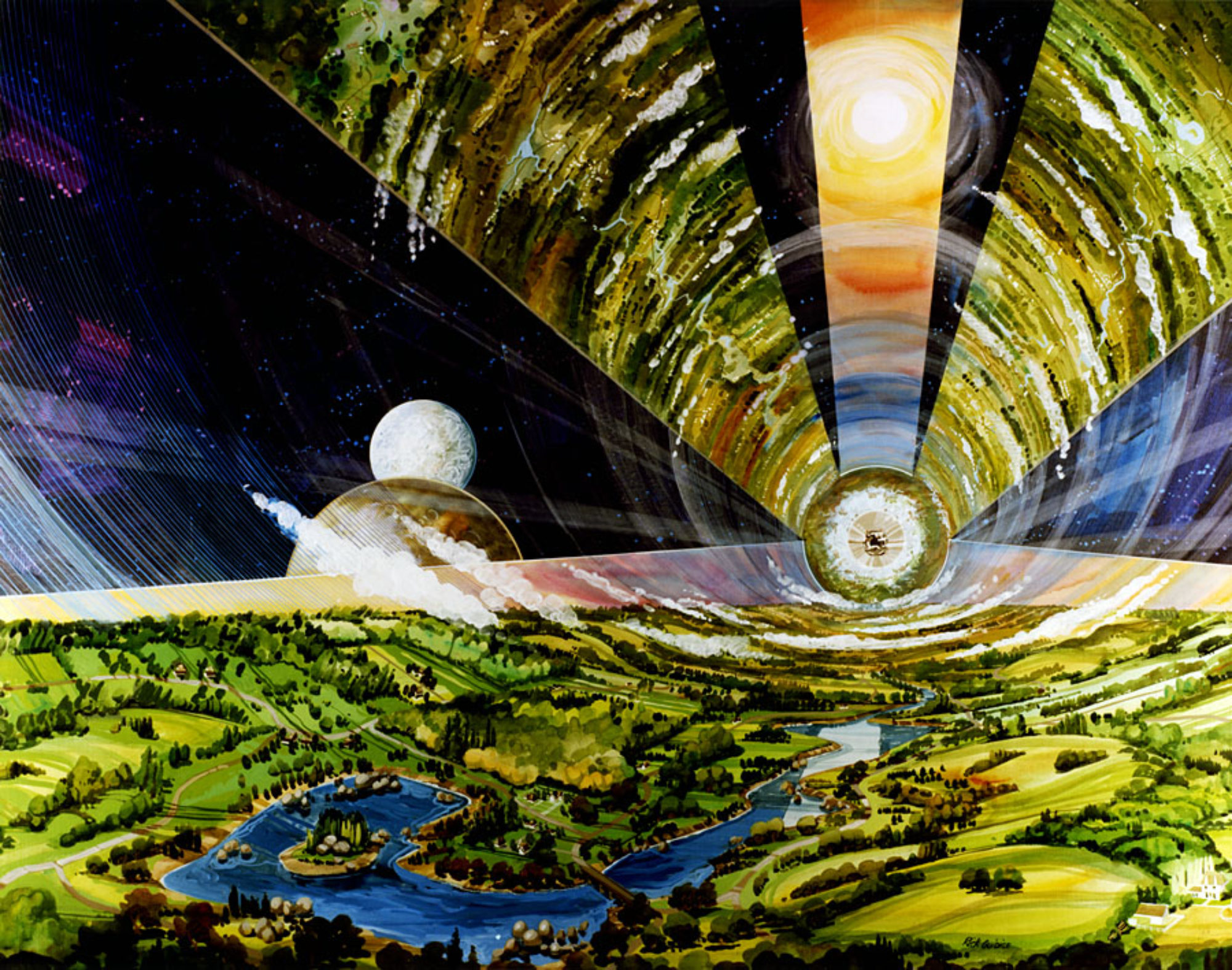

Developing the business case for lunar water is the first step in rapidly bootstrapping an off-Earth economy. Metzger has written about this previously where he sees robotics, 3D printing and in situ resource utilization being leveraged to accelerate growth of a solar system civilization.